Researched and Written by Matthew Scarlino.

This article was originally written in November 2018, with a version featured on TPS News.

One hundred years ago, the people of Toronto and its police service would experience the crucible that was the First World War. It was perhaps the most trying time the Toronto Police Service has experienced in its history. Canadians far and wide are reflecting on the experience of that war, the human cost of the victory, and what it meant for Canada going forward. In anticipation of Remembrance Day 2018, the centennial of the victory of that war, we would like to honour the memory of the men and women of the Toronto Police, and the part they played serving the residents of Toronto at home, and serving Canada abroad.

Part 1: The Home Front – A City at War, a Force under Strain

(City of Toronto Archives Fonds 1244, Item 734)

When the biggest war the world had yet seen broke out in August 1914, the Toronto Police Force, as it was then called, was policing Canada’s second-largest city with 626 sworn officers of all ranks, two pioneering “police women” (Mary Minty and Maria Levitt), 3 surgeons, 3 stenographers, two matrons and a censor. When Canada declared war on the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary after Belgium and France were invaded, dozens of officers went on leaves of absence to enlist. Staff shortages forced a further slew of volunteers to resign completely from the department in order to join the colours (graciously, the Police Commission would re-hire them after the war, including many wounded men). By war’s end 155 members had enlisted. This constitutes close to 25% of the pre-war strength of the department. And with the average age of a 1st Class Constable in Toronto being 42.9 years old in 1910, it is clear that a huge proportion of the force’s young, fighting-aged males were away.

Fortunately, while short-staffed, crime in the city went down in the months after war was declared in an apparent sign of civic unity. Concerned about the “home front”, the force immediately trained its officers in the use of military rifles, hired new special constables to help protect critical infrastructure, and stepped up patrols standing on guard against enemy spies and agents believed to be operating in the city. In 1915, when armouries in Windsor and railroads in New Brunswick were bombed by German spies, patrols, and anti-German and Austro-Hungarian sentiment and suspicion only intensified. There were 3 cases of high treason in the city, and in December 1915, Mayor “Tommy” Church announced German spies had been discovered applying to the Toronto Police Force. No attacks would materialize in Toronto.

(Author’s Collection)

Canada’s national policy at the time, under the War Measures Act, was to unjustly intern thousands of recent immigrants and labourers from enemy countries on arbitrary grounds due to these suspicions. In Toronto the internees were housed at Stanley Barracks and guarded by the military. Though most would be “paroled” by 1916 in order to work, they were still required to report to local police. Therefore, the Toronto Police Force participated in the registration and monitoring of the so-called “enemy aliens” by Detective staff, and the arrests of those who contravened the Act. The Force also seconded some officers to the Enemy Alien Office. The perhaps less-than-impartial P.C. Angus Ferguson, back from the war after having been gassed, imprisoned and having his leg forcibly amputated by his German captors after the fighting at St Julien, was accommodated with such a desk job.

(City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 848)

As the years went on, the officers who remained on the home front found themselves policing an increasingly rough and crowded city, now swelling with soldiers, nurses, newsboys, war industry workers and others. “The presence of a large number of soldiers in training” – Chief Henry J Grassett reported – “is taken advantage of by street walkers for solicitation”. Around the city, military camps and hospitals as well as munitions plants, shipyards and airplane factories sprang up. Roads were clogged with everything from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles, streetcars and military trucks. In January 1916, the Chief would be knighted by King George V, for his efficiency in policing the city in this challenging environment.

Keeping the peace between over-worked labourers, elites, soldiers (both raw recruits and battle-hardened veterans), malingerers and criminals was no easy task for the constables on the beat. Officers would be injured patrolling these chaotic roads – such as Constable Percy Fleming, severely injured in August 1916 when launched from his motorcycle so hard in a head-on collision that the soles of his boots were ripped off. Other officers would be wounded in assaults, civil unrest, and even shootings – officers such as Mounted Constable George Tuft, dragged from his horse and beaten during a March 1916 riot between soldiers and prohibitionists, or Constable John May, shot through the forearm in May 1918 while confronting car thieves in Sunnyside. There was also no shortage of courage at home, like Constable William Garrett who, in January 1915, arrested Private Douglas McAndrews, a local soldier on a shooting rampage around Yonge Street; or P.C. Medhurst promoted for bravery in June 1915 for daring attempts to rescue victims of a fiery industrial explosion in West Toronto.

(City of Toronto Archives. Fonds 1244, Item 969A)

By 1917, losses from the Somme offensive the previous year had created a significant manpower shortage among the Canadian Expeditionary Force, only to be worsened after costly victories at Vimy Ridge and beyond. The Chief reported that the strength of the force had decreased by 24 compared to the previous year (with most of the men joining the military for overseas service), and that the vacancies would not be filled. The Toronto Police Commissioners gave the officers a temporary raise – but then cancelled their weekly day off. To make matters worse, after reducing their shifts to 8 hours, their work days were again increased to 12 hours. Also, in order to support their colleagues fighting in the trenches, all officers voluntarily donated one days’ pay a month to the Patriotic Fund – which in one ten-month period had raised $20,000. The officers even found time around their long shifts to plant Victory Gardens around their police stations. In 1917 alone they cultivated 22 acres of land, and by war’s end they had donated 1,820 bags of potatoes to military hospitals in the city, as well as other hospitals and charities.

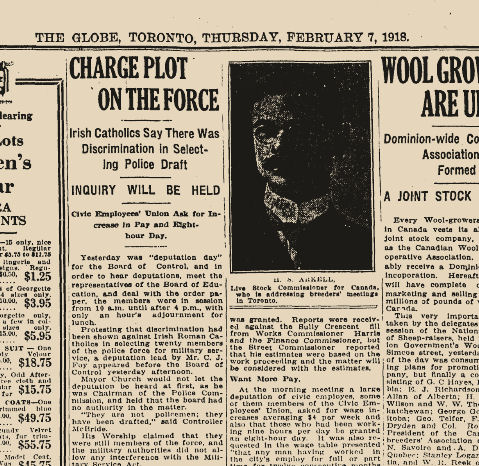

(Toronto Public Library, Historical Newspapers Collection).

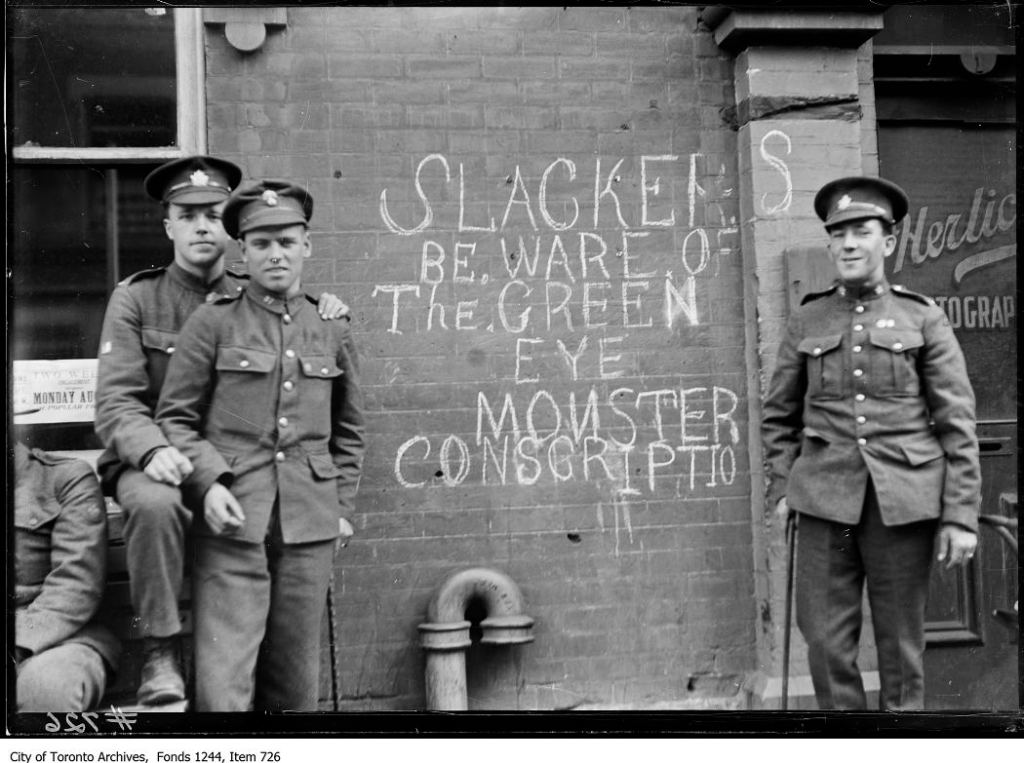

Due to the mounting losses overseas, the Canadian government enacted the Military Service Act towards the end of 1917, allowing for conscription of military-aged men. While at first it seemed the police force was an essential occupation, it too would have to provide a list of names of eligible men “most easily spared”, from which twenty would be drafted. When screening out officers who were sole providers for their families, had medical conditions or were over-age, had siblings killed or wounded overseas, or other considerations, this left about 40 officers to choose from. A scandal soon erupted in the religiously divided city of the time. Constables of Irish Catholic backgrounds alleged in the newspapers that the list of names forwarded was overwhelmingly Catholic, though they only made up a small percentage of the largely Protestant police force. Constable James Lee, who had already been granted an exemption by the military tribunal, even had his exemption papers seized by a Deputy Chief in order to be named to the list of available men. Tempers flared over the sectarian problems in the department. A Board of Inquiry was to be established, but cooler heads prevailed, and only 5 of the 18 men on the force’s final list who would eventually called to serve were of the Catholic denomination.

(City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 726.)

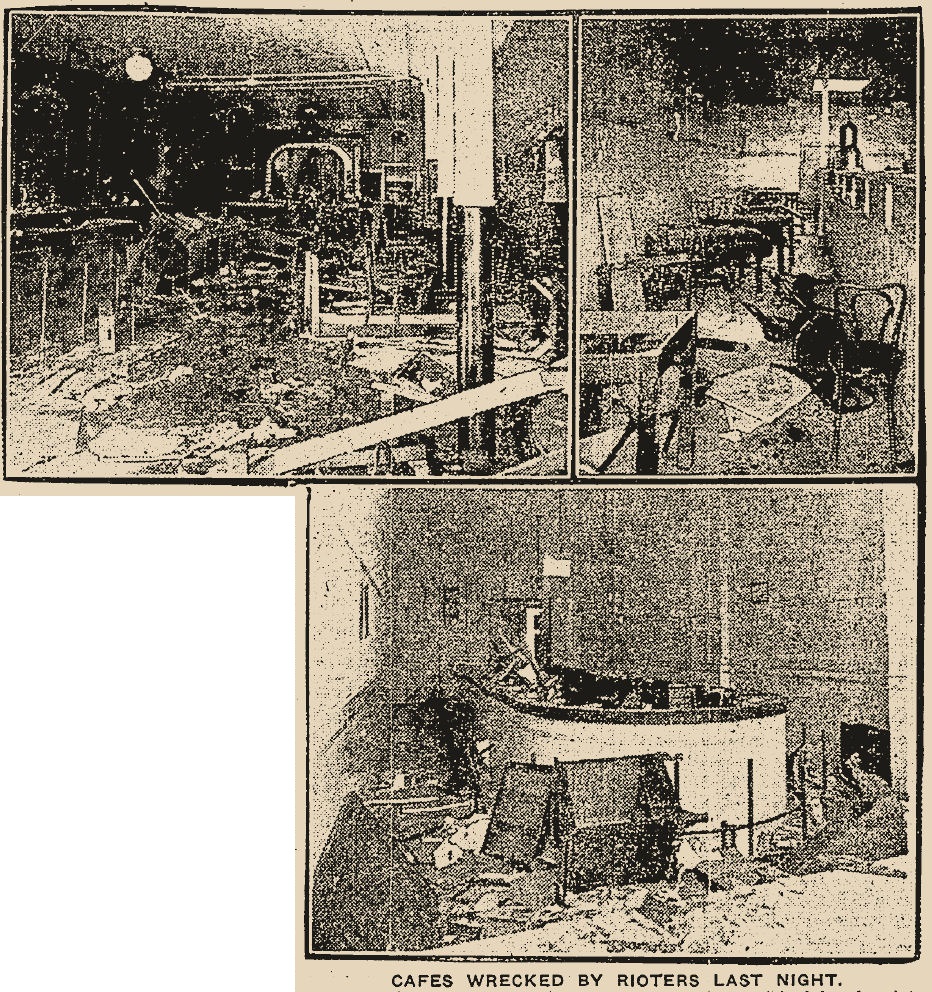

Later, in early August 1918, what would be dubbed the Toronto Anti-Greek Riots broke out. It raged for three days and to this day is the largest riot in the city’s history. It began on a hot summer weekend when many veterans descended on the city for the first-ever national congress of the Great War Veterans Association, with grievances of returned soldiers a main topic of discussion. When a disabled soldier was denied service at the Greek-owned White Star Café on Yonge Street for being drunk and abusive to staff, he was removed and police were called. This area was home to a veteran’s hospital and many boarding houses in which returned soldiers lived. Tensions had already existed there, as a number of Toronto’s Greek immigrant population refused to join the Canadian forces due to their home country being officially neutral, fearing a scenario where they would be interned or have to fight their own countrymen if Greece joined the Central Powers. However many Toronto Greeks did serve, and Greece did join the Allies after all in mid-1917. Many of the local Greek business owners contributed regularly to the Patriotic Fund.

None of this mattered to the angry mob of soldiers who gathered and destroyed the business after hearing about the incident. The group of soldiers and sympathetic civilians continued to grow into hundreds, and later thousands, and went on to attack the many other Greek-owned restaurants downtown. The police attempted to disperse the crowds but believed the military police had jurisdiction over their soldiers and asked for help which never came. Many businesses were destroyed and the police were under scrutiny in the press for their ineffective response.

The following evening, soldiers with bugles played the “Call to Arms” and crowds gathered for another night of Anti-Greek destruction. After ringleaders of the mob were arrested, a crowd formed around No. 1 Police Station near King and Church Streets where they were held. The crowd tried to storm the police station and free the men. Constables ran out of the station and led a baton charge to disperse the crowd, while mounted officers staged nearby did the same, trapping the rioters and any onlookers that had gathered. While the Toronto Daily Star reported that the “officers used their batons mercilessly on everybody within reach,” the soldiers fought back, arming themselves with bricks and other missiles. The soldiers-turned-rioters regrouped at “Shrapnel Corner,” Yonge and College Streets, but were again charged by the Mounted Squad. More crowds would attack the No. 2 Police Station at Bay and Dundas Streets, where officers repulsed three separate attempts to storm the station. Everywhere the soldiers re-formed they were met by baton-wielding police. Pitched battles were fought into the night, the largest of which was a decisive engagement at Yonge and Queen Streets. A little after 2 a.m., all was finally clear. The police had suppressed the riot in which thousands had taken part. Twenty businesses were destroyed, 500 people were injured, and at least ten were arrested. The damage was so extensive that the area was mostly abandoned by the Greek people who then re-settled along Danforth Avenue.

As 35 people had been seriously injured during the police response, an inquiry was held. Many policemen were injured too, such as Patrol Sergeant Hobson who received a brick to the head while on his horse. Many complaints of excessive baton use were heard and two inspectors, a patrol sergeant and a constable were dismissed from the force. However, five officers were promoted and seven received Merit Marks for their exemplary performance in the chaos. Daily headlines would keep this incident in the minds of Torontonians for months to come. News of mounting victories overseas known as “Canada’s Hundred Days” offensive, however, would bring welcome relief.

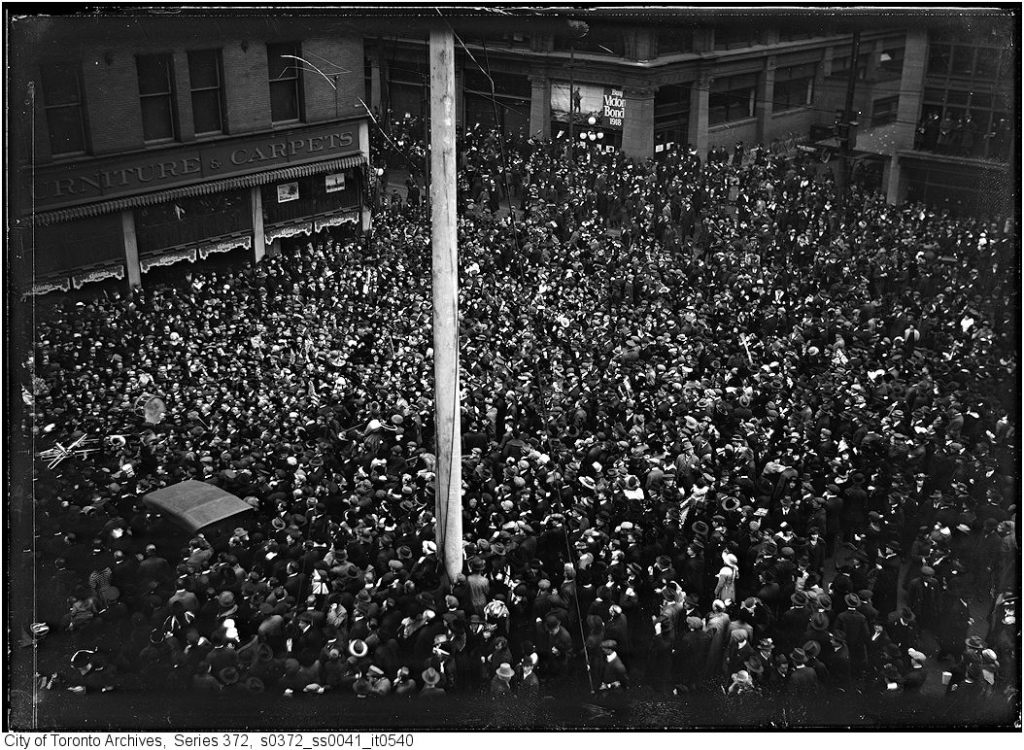

(City of Toronto Archives, Series 372, Item 0540)

At 11 o’clock on the 11th day of the 11th month – November 11th, 1918, church bells rang out and newsboys sang headlines of an Armistice. The guns in Europe fell silent and the war was over. Canada and her Allies were victorious. Crowds packed the streets shoulder-to-shoulder, and Chief Grasett observed: “The armistice was celebrated with great rejoicing by the entire population, whose behavior in the streets was admirable, giving the police little trouble with the good natured crowds who did not go home till well on through the night.” Police and citizens celebrated openly in the streets and breathed a collective sigh of relief.

All was not yet well however. Merely a week later, on the night of November 18th, 1918, Acting Detective Frank Albert Williams was shot through the heart while investigating a suspicious person in a stable near King and Bathurst Streets. The killer gunman, Frank McCullough, argued at his trial that he shot Williams out of self-defence because the officer was armed with his baton, referencing the rhetoric that had been playing out in the media. It didnt work, and he was sentenced to hang eight months later – where yet another riot broke out, by a large group of supporters of McCullough who agreed the man was justified. It can therefore be said that the Toronto Police Force’s first line of duty death also had its roots in the war.

In December 1918, with the war in the rear-view mirror, the membership of the Toronto Police Force – scrutinized in the press; overworked, understaffed and underpaid due to the war shortages; and having felt the sting of its first line of duty death – wanted to unionize. This was denied, and a sizeable contingent of the department went on an unheard-of strike. The strike lasted for four days. Though a failure in the short term, negotiations in the following year would see the Toronto Police Association born, in 1919. Together with the reforms to the Toronto Police Commission (the precursor to today’s Police Services Board), made after the previous year’s riot inquiry, permanent changes were made that would secure a better future for the working conditions of the constables on the beat. With many experienced Toronto Police officers returning from the front and rejoining the ranks of the department, together with the injection of many new recruits, the last strenuous chapter of the war on the home front was over. Membership in the Toronto Police Association, the Amateur Athletic Association, and War Veterans Association were growing. Morale was restored. Swagger returned to the step of the constables on the beat just in time to face the Roaring 20s and new challenges ahead.

PART 2: From blue to khaki: remembering the sacrifice overseas

Apart from the important work the force did on the home front, the 155-member strong Toronto Police contingent that enlisted in the military for active service overseas punched well above its weight. They were spread throughout many different units in the Canadian and British forces – mostly in the infantry and artillery, but also the cavalry, the military police, and logistical and medical units.

(City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 759.)

The police officers made natural leaders, and many held important leadership positions. Seventeen would end the war as Sergeant-Majors, the highest position for an enlisted soldier. Fifteen others would have the honour of being commissioned as officers from the ranks, many for bravery. For their valour, Toronto Police constables were awarded three Distinguished Conduct Medals (DCM), a rare warrant officer’s Military Cross, seven Military Medals, a Meritorious Service Medal, two Mentions-in-Despatches, and a Serbian Silver Medal for Bravery. The citation for Mounted Squad officer Thomas Crosbie’s D.C.M., received for actions during the Second Battle of Arras while serving with the Royal Canadian Artillery, is representative of the courage of the police contingent:

“For gallantry and devotion to duty. About 9am on 28th August 1918, a large enemy shell landed in [an ammunition] dump located at the Arras-Cambrai Road between Arras and Faub St. Sauveur killing seven men and wounding five of the dump personnel. He was blown twenty to thirty feet by the explosion and wounded slightly, but with great gallantry and utter disregard for personal safety he immediately got water and put out the burning ammunition and prevented more casualties. Notwithstanding his wounds and the severe shock he had received he continued to issue ammunition until relieved. His example throughout was most inspiring to the men.”

One of three Toronto constables to receive the Distinguished Conduct Medal, second only to the Victoria Cross. Crosbie would rise to become the Inspector of the Mounted Squad after the war.

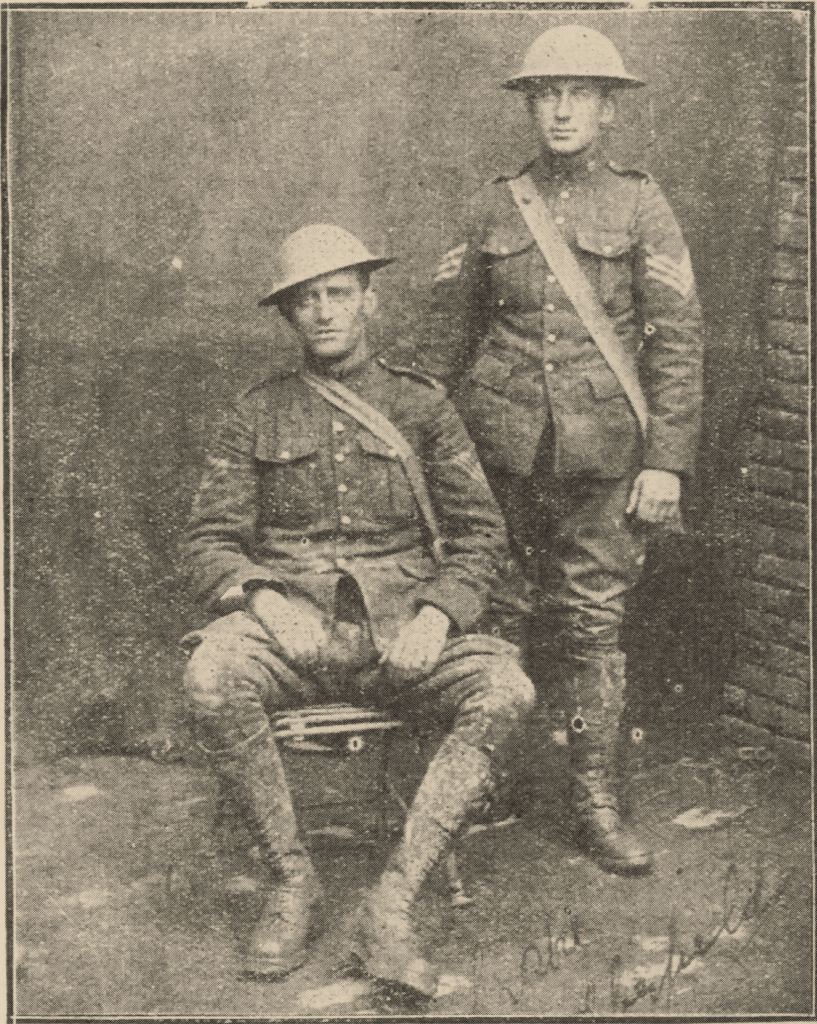

(Toronto Public Library, Historical Newspapers Collection)

Twenty-seven members of the Force would be killed overseas. All but one of the nineteen police horses donated for service with the Canadian Artillery, such as Canada and Crusader, St. Patrick and Vanguard, would die too. Fifty-seven Toronto policemen were wounded in battle, some twice or even three times – Constable “Len” Bentley, was wounded two times in the chest and later shot through the nose. Seven men would be diagnosed with Shell Shock (an ancestor of today’s Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder), like Constable James Farlow, whose doctor noted he was “broken by dreams of France” after he was buried alive by a shell on the Somme and later gassed at Vimy Ridge. Two others would be captured and sent to Prisoner of War camps after falling wounded at the Second Battle of Ypres, like Old No. 4 Station’s Harry Rainbow who languished behind barbed wire for years.

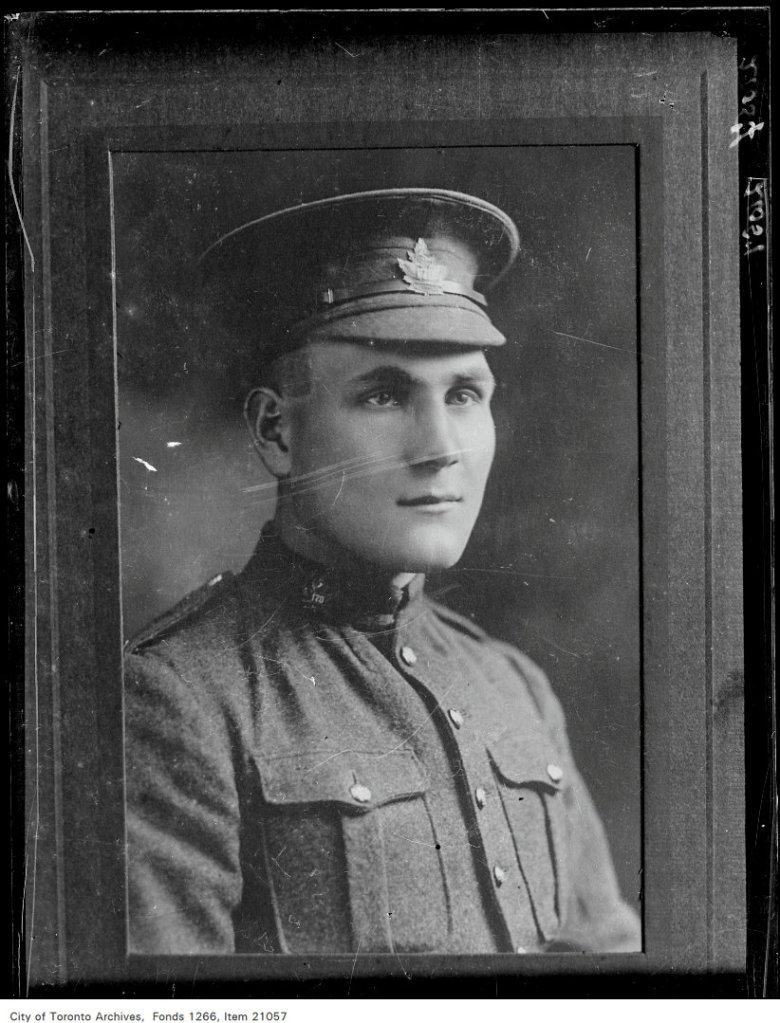

(City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1266, Item 21057.)

The surviving men that returned to the Toronto Police Force, as well as new veterans hired after the war, formed the Toronto Police War Veteran’s Association to support each other and honour the fallen. The memorial plaque in the lobby of Toronto Police Service Headquarters was erected so the names of the fallen would never be forgotten. Over time however, details were lost and the life stories of the Toronto Police war dead have mostly slipped away from our collective consciousness. Thanks to the veterans’ foresight in erecting the plaque, and recently digitized military personnel service files at Library and Archives Canada, their stories can finally be told. On the eve of the 100th anniversary of victory in the First World War, we re-commit to remembering their lives and honouring their sacrifice.

Read more about the Toronto Police First World War fallen:

Sources and further reading:

- H. Grasett – Annual Report of the Chief Constable of the City of Toronto, Nominal and Descriptive Roll of the Toronto Police Force. (1914, 1915, 1916, 1917,1918 and 1919 editions).

- Library and Archives Canada – Personnel Records of the First World War; Circumstances of Death Registers; Honours and Awards Citation Cards 1900-1969

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission – Casualty Details.

- Toronto Public Library – Historical Newspapers Collection: 19140803 The Globe – Toronto Policemen May Go To Front; 19140923 The Globe – Drill and Shooting for City Officers; 19150123 Toronto Daily Star – Soldier Ran Amuck, Wounded Small Boy; 19150514 Toronto Daily Star – Toronto Policeman Missing; 19150621 Toronto Daily Star – Windsor Armouries and Walkerville Plant Attacked; 19151101 The Globe – Have Leg Amputated, or Be Shot; 19151115 The Globe – Foe Deny Atrocity; 19151201 Toronto Daily Star – Mayor Says German Spies Try to Get on Police Force; 19160101 The Globe – Many Canadians are Included in the King’s New Years Honor; 19160126 Toronto Daily Star – $20,000 from the Police; 19160314 The Globe – Soldiers as Police for Men in Khaki; 19160405 The Globe – Gave Way to Fear of Being Killed by Mob; 19160808 The Globe – Policeman Hurt Badly When Auto Hits Cycles; 19170110 Toronto Daily Star – Toronto Soldiers Given Commissions; 19170207 Toronto Daily Star – Letters: Policemen’s Pay; 19171116 Toronto Daily Star – 14 City Policemen Ordered to Put on Khaki; 19171117 Toronto Daily Star – Of 57 Policemen Up on Friday, 36 Must Serve; 19180123 The Globe – Says Austrian Tried Bribery, Selects Police to Put on Khaki; 19180207 The Globe – Charge Plot on the Force: Irish Catholics say there was Discrimination in Selecting Police Draft; 19180501 Toronto Daily Star – Policemen Get in Spuds; 19180928 The Globe – Policemen Tell Their Story; 19181003 The Globe – From Inquiry to Inquiry Mounted Officer has to Explain to Chief as well as Police Board; 19181101 The Globe – Youth Fires At Constable; 19190301 Toronto Daily Star – Eight Hour Day for Policemen.

- B. Wardle – The Mounted Squad : An Illustrated History of the Toronto Mounted Police 1886-2000.

- J.M.S. Careless – Toronto to 1918: An Illustrated History.

- J.L. Granatstein – Hell’s Corner: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Great War 1914-1918.

- M. G. Marquis – Working Men in Uniform: The Early Twentieth-Century Toronto Police

- The Canadian Encyclopedia [online] – Internment in Canada

- J. Burry/A Burgeoning Communications Inc. – Violent August: The 1918 Anti-Greek Riots in Toronto. [ Documentary Film]