Researched and Written by Matthew Scarlino.

This article was originally written in June 2019 and versions were published in Blue Line Magazine and featured on TPS News.

It was spring 1944. The Second World War had been raging for four and a half years. Most of Europe lived under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler.

Millions of Jews, visible minorities, queer people, political dissenters, and people with disabilities were being rounded up and sent to death camps. Rights and freedoms disappeared and occupied peoples were forced to work towards the Nazi war effort. The Western Allied armies of Great Britain (including Canada and other Commonwealth nations), France, Belgium, The Netherlands, and other European nations, had been pushed out of mainland Europe since 1940 when Nazi Germany invaded in their blitzkrieg – “lightning war”. The Western Allies escaped to Britain, where they remained under attack from the air, but persevered. When the Americans joined the war, they too would sail to England and prepare to fight.

Meanwhile, the Nazis fortified Europe using slave labour to build the Atlantic Wall, coastal defences made of concrete bunkers, weapons pits, landmines and other defences to make re-invasion impossible. The Western Allies instead invaded through Italy in 1943, but the narrow and mountainous terrain heavily favoured the defenders – casualties were high and progress was slow. In the east, the Soviet Union was also taking heavy losses pushing Nazi forces out of Eastern Europe. The situation was bleak and there needed to be a breakthrough elsewhere.

A plan was made to form a massive armada of ships, planes, and troops and invade Occupied France across the English Channel at Normandy. Five beaches would be assaulted, the Americans and British responsible for two beaches each, and the Canadians responsible for the last beach – code-named “Juno”. It wasn’t clear if the plan would work and casualties were expected to be extremely high. After bad weather postponed the attack, it was finally settled that it would take place on June 6, 1944, code-named “D-Day”.

On June 6, 2019, Canadians across the country are commemorating the 75th anniversary of the daring invasion, which marked the beginning of the end of World War II. The successful Normandy Campaign commenced a drive to Germany that would see the war end in less than a year. And just like the many Toronto policemen who fought in the First World War, 235 members (men and women) of the Toronto City Police Force, would leave to serve in the Second World War(1). Many of them took part in the D-Day invasion.

This is the story of a half-dozen police officers, just a small sample of the many Toronto Police members who contributed to victory in the Normandy Campaign at sea, on land, and in the air.

At Sea

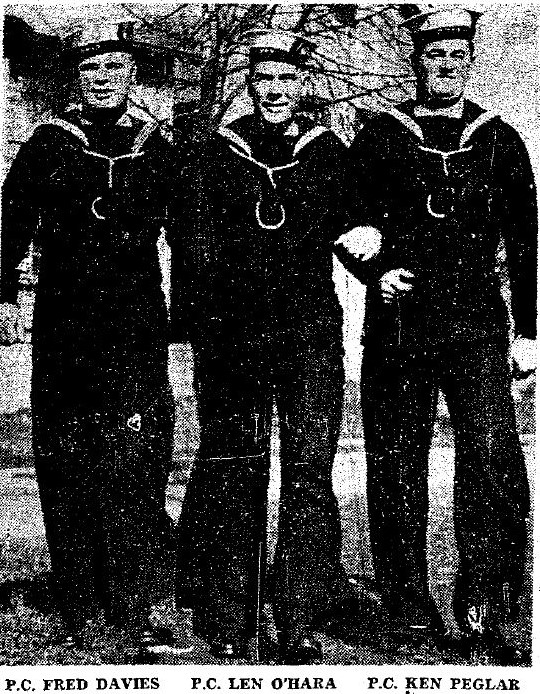

Some of the first Toronto Police members in action on D-Day were three burly constables aboard the HMCS Skeena. Fred Davies, Len O’Hara and Ken Peglar were all towering policemen who had joined the Royal Canadian Navy together as stokers – whose main duties were to feed coal into the ship’s boilers – in 1940. Deputy Chief Charles Scott described them as “outstanding” track and field athletes in the Toronto Police Force Amateur Athletic Association, who would be “an asset to any ship.”(2)

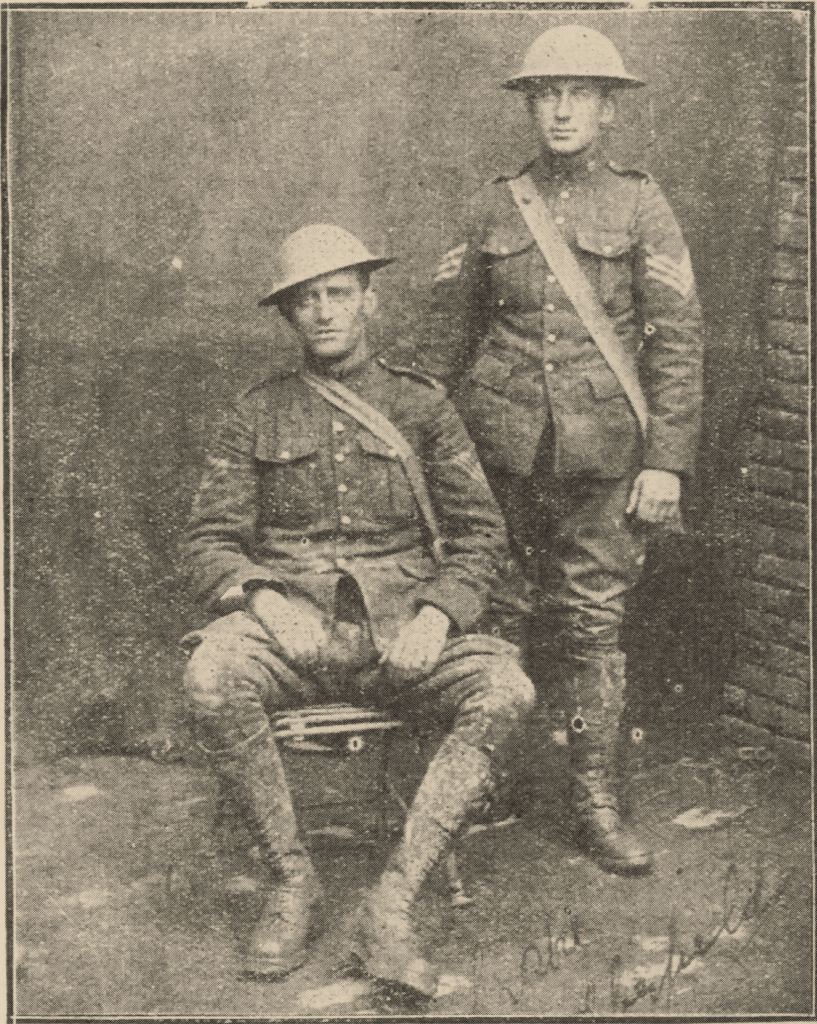

Constables Frederick Davies (#284), Leonard O’Hara (#55) and Kenneth Peglar (#108) in their Royal Canadian Navy uniforms, as they appeared in a 1942 edition of the Toronto Daily Star

The men had survived terrifying sea battles in the years leading up to this momentous day, including being involved in the first sinking of an enemy submarine by Canadian forces. While on convoy duty, on the night of September 8 & 9, 1941, the ships they were protecting were attacked by a “wolfpack” of German submarines known as U-Boats. In the epic 66-hour battle that ensued, the Skeena launched depth charge after depth charge in chaotic fighting in which Constable Peglar was wounded by a powerful blast that launched the 6’4”, 245-pound policeman through the air into a bulkhead. (3) When the smoke settled two U-Boats were sunk at a loss of 16 merchant ships.

Now veteran seamen, they were on board one of the 63 Canadian warships participating in the greatest sea-borne assault in history. In the hours leading up to the D-Day invasion, the trio toiled below-deck stoking the steam engines in the sweltering boiler rooms of the Skeena. Their destroyer was paving the way for the invasion force by clearing the sea lanes of enemy ships, and starting at 5:45 a.m., bombarding the coastal defences where enemy machine guns and artillery were laying in wait, zeroed-in on the landing beaches. (4)

About two hours later, Canadian assault troops landed at Juno Beach into murderous fire from the entrenched enemy who by now were expecting an attack.

While the first waves of Canadian infantry and tanks fought through the beaches and into the town, the SS Sambut was just sailing out of England’s River Thames, carrying reinforcements for the blood-stained sands of Normandy. It was taking an indirect route to avoid detection. Among the vehicles, munitions, and troops on board was a 28-year-old Lance Sergeant in the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps (RCASC) named Clarence Verdun Courtney. (5) Following in the footsteps of his father, Courtney joined the Toronto Police Department, graduating as a constable in 1938. After three years of service, he put his career on hold and answered the call to arms to defeat tyranny. He rose quickly up the military ranks and passed specialized training including advanced infantry training, platoon support weapons, mine detection and clearing and military motorcycle riding. He was posted to No. 84 Company RCASC, part of the 2nd Armoured Brigade, and was tasked with providing logistical support to tanks in battle.

While crossing the Straits of Dover, the Sambut encountered fire from German coastal batteries in the nearby French city of Calais, and at 12:15 p.m. she was hit in the side by 15-inch shells. Shrapnel tore into Courtney’s abdomen, and the fuel and trucks on deck around him were set ablaze, shortly followed by the explosion of an ammunition cache in the ship’s hold. In a chaotic scene, soldiers began throwing ammunition off the side of the ship, while secondary explosions sent shrapnel flying around them. (6) A British medical officer found Courtney and began dressing his wounds. Within 15 minutes, however, the order was given to abandon ship.

While thoughts surely flashed through Courtney’s mind of his wife Margaret and their peaceful home on Glendonwynne Road, he was helped to life rafts by his comrades. He then clung to the side of a crowded raft as long as he could, but the young Lance Sergeant succumbed to his wounds and slipped into the sea,(7) robbed of any chance to fight back.

Courtney was one of the hundreds of Canadians who died that day. He is commemorated on the Bayeux Memorial in France.

ON LAND

In the following days, the Allied soldiers established their toe-hold into occupied France and pushed out from the beaches, fighting through the towns, fields and hedgerows of Normandy. The weaker German coastal defence troops were being reinforced by crack tank divisions from further inland.

Amidst the Canadian forces fighting their way inland was Harry Lee Smuck, a captain in the 6th Canadian Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars) – a tank unit. The 41-year-old was a Patrol Sergeant in the Toronto City Police Force, who joined back in 1926 and served at the Belmont Street and Claremont Street stations as well as the Mounted Unit. At 5’10 and ¾”, the fair-haired blue-eyed policeman was short compared to his colleagues in an age of height requirements on the force. (8)

To ‘do his bit’, Smuck enlisted in the 1st Hussars soon after the war broke out, and said goodbye to his wife Hettie, and children William and June. As a young man, Smuck had served seven years in the Canadian militia with the Royal Canadian Dragoons, another armoured outfit. Due to his police service and prior military service, he rose quickly through the ranks and was commissioned as an officer.

Harry Smuck and his troops had made the hellish assault on Juno Beach, in specially equipped Sherman tanks that could operate while partially submerged underwater. Landing near Courseulles-sur-Mer in the second wave of the attack, he and his “C” Squadron tanks put their 75mm cannons and machine-guns into action to the relief of the battered infantrymen on the shore. They fought hard breaking out from the beach, through intense street battles in town and into the fields beyond. (9) The 1st Hussars, through skilful deployment of tanks led in part by Smuck, were the only element of the entire Allied invasion force to meet their final D-Day objective. But there would be no time to rest.

After five days of fighting, Smuck received orders on the morning of June 11, 1944, that his tanks would support the Queen’s Own Rifles in an assault on German troops occupying the town of Le Mesnil-Patry. Unbeknownst to them, their radio codes had been captured some days earlier and the enemy was listening. When the attack set off in the afternoon, the Germans held their fire until the Canadians were halfway into the town. (10) The Hussars and Queen’s Own were suddenly met by tremendous machine-gun and mortar fire from a great number of troops lying in wait in the hedgerows, haystacks and buildings of the town. In response, Smuck’s tanks unleashed devastating fire (11)on the enemy and the survivors were beginning to flee. The tanks pressed on toward the village, where they found another trap waiting. As they approached, “B” Squadron started taking fire from 7.5cm anti-tank guns, which were knocking out the Canadian tanks. Then, powerful German Panzer IV tanks took the field and engaged them – the 2nd Battalion, 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend, a fanatical Nazi unit made up of experienced fighters and members of the Hitler Youth, was counter-attacking. A fierce tank battle ensued. Smuck and his ‘C’ Squadron tanks were ordered forward into a field of burning tanks,(12) and continued the fight.

In the chaos that followed, the Canadians were ordered to withdraw. Of the over 50 tanks from the 1st Hussars that went into action, only 13 made it back. Many men were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. Some, like Harry Smuck, were simply listed as missing. In the first six days of the Normandy campaign, over 1,000 Canadians would be killed, and over 2,000 wounded. (13)

IN the air

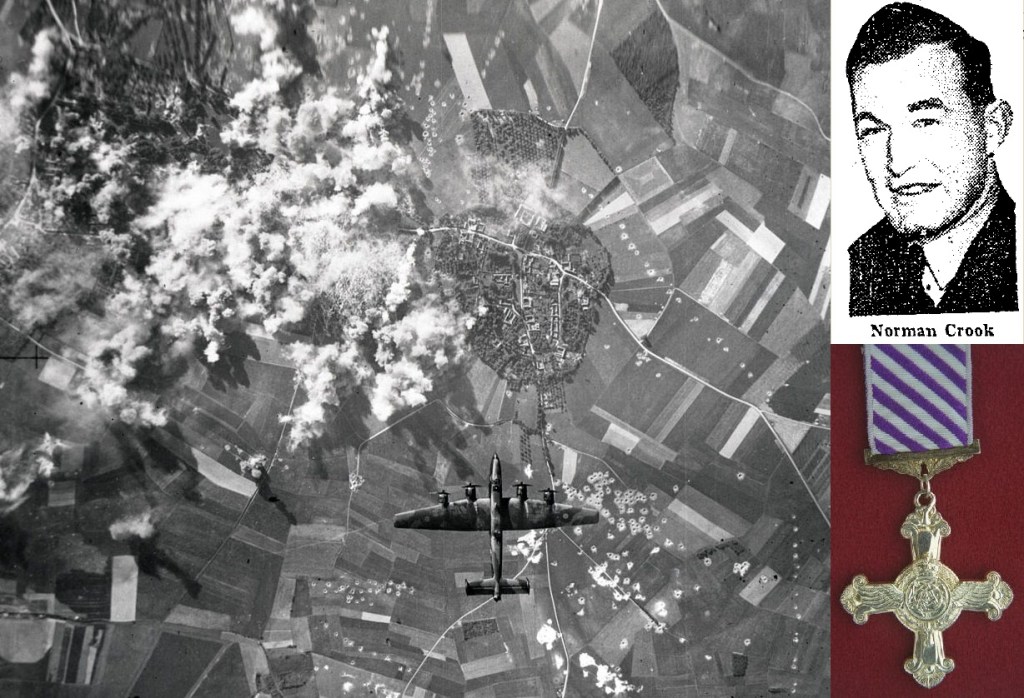

Pressing on the attack in the air was a motorcycle cop from East York,(14) Constable Norman Crook, flying with No. 433 “Porcupine” Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Crook joined the air force in the summer of 1942 and by D-Day, was a navigator on a Halifax bomber plane on an overnight mission to drop sea mines into the English Channel to protect the invasion fleet.

After the Allies established a foothold in France, Crook’s squadron went to work bombing enemy troops, positions, railways and other infrastructure that could be used to send reinforcements against the Canadians.

One such mission took place on the night of June 28, 1944. Crook’s Halifax Bomber, tail number LV-839, took off on a bombing run to Metz, France, piloted by Hamilton McVeigh of Port Arthur, Ontario. En route to the fortified city, Crook and his crew suddenly encountered tracer fire coming out of the darkness – three German Ju-88 night fighters were attacking the slower bomber plane. After evading three waves of attacks from the fighter planes, the bomber was finally hit while flying in an evasive corkscrew manoeuvre. “The one shooting at us was just a decoy,” recounted Crook, “we were too busy watching him to see the guy behind. All of a sudden we got walloped. The first shell missed the rear gunner by inches and lopped off one of the rudders. Another shell went through the wing – then another, and finally one wing tip was chipped off.”(15)

The crippled aircraft, with its massive bomb load still on board, went into a tight spin at 13,000 feet in the air. The engines were failing and the pilot ordered the crew to bail out of the aircraft, which some started to do. Crook, however, made his way to the pilot, McVeigh, wanting to say goodbye to his friend before parachuting out. At that point he changed his mind and decided to stay on board – meanwhile McVeigh levelled off the aircraft at 6,000 feet. Crook, the plane’s navigator, set a course for England, to an alternate airfield with long dirt runways suitable for a crash landing. Two minutes after midnight, the aircraft made a hard 155-mph landing at Woodbridge, England, the remaining crew safe and their ordeal over. (16)

Crook’s action that night would later be recognized by the second highest award of bravery an airman could receive. His recommendation read, in part: “ …when attacking Metz his aircraft was attacked three times by fighters and was very severely damaged. So much so that two members of the crew abandoned on order of the Captain, and the aircraft lost 7,000 feet before control was regained. At that time the port outer engine cut so the bomb load was jettisoned and a course set for England. Pilot Officer Crook cooly and skilfully navigated his damaged aircraft back to a diversion base, avoiding the heavily defended areas en route, and a high-speed landing was made at an emergency landing field.” For this action and his overall flying record, he would receive the Distinguished Flying Cross.

towards freedom and justice

The fighting in Normandy, France would go on until the end of August 1944. It marked the turning point in the war and from there Canadians pushed on through Belgium, the Netherlands and finally into Germany. The Nazis would surrender unconditionally in May 1945, and the true extent of their evil deeds became known – concentration camps were discovered, liberated and their victims freed. Millions who had lived under oppression would start to rebuild. The rule of law was re-established and war criminals were put on trial.

One such war criminal was the Nazi General Kurt Meyer, who was tried by a Canadian War Crimes court. It was during these proceedings that the fate of Patrol Sergeant Harry Lee Smuck was discovered, thanks to the Canadian War Crimes Investigation Unit. During the battle for Le Mesnil-Patry, Smuck’s tank had been knocked out by enemy fire and he and his crew, some wounded, managed to bail out and make a break for their lines. They became separated in a firefight and Smuck and one of his men hid under another destroyed Canadian tank to re-group.

Suddenly, the pair were swarmed by enemy troops and they decided to each make a run for it. Captain Smuck was captured and marched off to a secluded area with other Canadian prisoners of war, including some of his own tank crew, also captured in the chaotic battle. Once there, Smuck and the other men were lined up, callously shot, and buried in a shallow grave. (17) It was an unjust end for a brave man.

General Meyer was found guilty of ordering the killings, and other atrocities. Though sentenced to death, another unjust turn of events would see him only serve five years in a Canadian prison before returning to Germany, and ultimately being freed by 1954. Smuck’s remains were re-interred at the peaceful Ryes War Cemetery in Bazenville, France.

The sacrifices that many Toronto Police members made during the Normandy Campaign should never slip from our memory. On this 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, let us pause to remember those who came before us and risked it all so that we could be free.

Sources and further reading:

(1) D. Draper. Annual Report of the Chief Constable of the City of Toronto for the Year 1939, Toronto: The Carswell Co Ltd City Printers, 1940.

(2) Toronto Daily Star 1940-09-14, p.15 “Policemen Join Up and Stick to Blue”

(3) R.H. Gimblett. The Naval Service of Canada p.90-91; Toronto Daily Star 1942-01-10, p.9 “Many Toronto Men Helped Skeena Beat Off Wolk Pack”; Toronto Daily Star 1942-01-03, p.7 “PC Fred Davies, et al”; Toronto Daily Star 1942-01-03, p.3 “Says 20 U-Boats in Pack of Which Skeena Sinks 3”

(4) Cobourghistory.ca/stories/hmcs-skeena; The Naval Service of Canada p.71-72

(5) Library and Archives Canada. Personnel File of B80413 Clarence Verdun Courtney.

(6) T. McCarthy. True Loyals – A history of 7th Battalion, The Loyal Regiment (North Lancashire) / 92nd (Loyals) Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery 1940-1946. Regimental History, Chapter 8: Disaster on the Sambut (Trueloyals.com/new-page-18)

(7) Library and Archives Canada. Personnel File of B80413 Clarence Verdun Courtney; Statement of Pte. J.S. Poulton, No 84 Coy, RCASC

(8) City of Toronto Archives. 1926 Nominal and Descriptive Roll of the Toronto Police Department.

(9) J. Marteinson & M.R. McNorgan. The Royal Canadian Armoured Corps – An Illustrated History. D-Day: The 1st Hussars and 7 Infantry Brigade. p.232-236.

(10) T. Copp. A Well Entrenched Enemy: Army Part 92 (Legion Magazine). Kanata: Canvet Publications Ltd, 2011.

(11) Library and Archives Canada. War Diary of the 6th Canadian Armoured Regiment(1H), June 1944.

(12) J. Marteinson & M.R. McNorgan. The Royal Canadian Armoured Corps – An Illustrated History. The Hussars at Le Mesnil-Patry. p.245-248.

(13) Veterans Affairs Canada – Normandy 1944 (veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/second-world-war/normandy-1944)

(14) Toronto Daily Star 1944-11-28, p.13 “4 for a Fight, 3 for a Trip, Need 120 Points for Leave”

(15) Toronto Daily Star 1944-11-28, p.13 “4 for a Fight, 3 for a Trip, Need 120 Points for Leave”

(16) Collections Canada. Operations Record Book of No 433 Squadron RCAF – June 1944 Summary of Events, p.6

(17) H. Margolian. Conduct Unbecoming: The Story of the Murder of Canadian Prisoners of War in Normandy. Pages 111-115, 235-237. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.