Researched and written by Matthew Scarlino.

This article was originally written in June 2020 for the Toronto Police Military Veterans Association.

Eighty years ago this week, a small number of Canadian soldiers landed at Brest to participate in the Battle of France, in what is now an obscure and little-known operation that took place in June 1940.

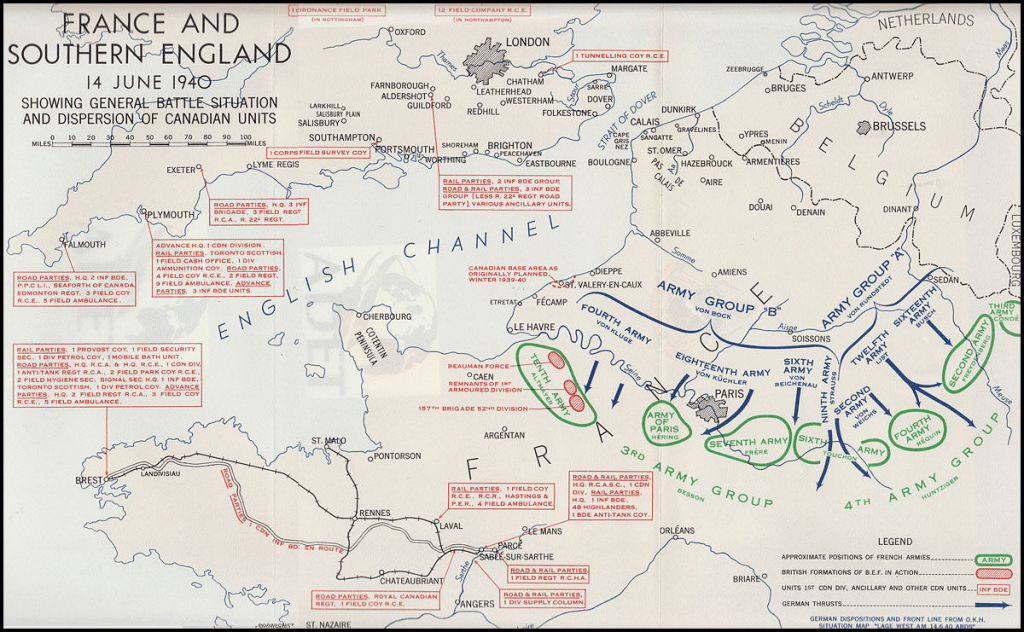

Just days before the Canadians landed, the nearly-destroyed British Expeditionary Force was miraculously evacuated from Dunkirk. The German army then pressed their attack against the remaining French Army south of the Seine and Marne rivers.

In a desperate bid to keep up a foothold in France, Britain committed its last two fully-equipped infantry divisions, the 1st Canadian and 52nd Lowland, as well as the 1st Armoured Division in a force now known as the “Second” British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The mission was to be kept secret to avoid detection by German forces. The 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade would spearhead their division, and advance parties landed at the French port city of Brest, on 12 June 1940. The orders for the operation, somewhat unclear, were to drive toward and reinforce the new French defensive position dubbed the Weygand Line. Or, “failing that, to join in the defence of the Breton Redoubt as a last fortified foothold on the continent” [Copp].

As could be expected, owing to the Toronto Police Department’s large and widespread contribution to the war, Toronto policemen were among the contingent. One such officer kept a brief diary during the campaign, which offers a rare first-hand look. Police Constable (709) James “Tiny” Small, joined the Toronto Police Force in 1921, walking the beat out of the old No. 6 Police Station (Queen & Cowan Ave) and later, motorcycle patrol. Small was also the Drum Major of the Toronto Police Pipe Band, which is still active today.

Small left the force for military service at the outbreak of war in Autumn 1939. Now, the 6’6” “Tiny” Small was a Warrant Officer and Acting Regimental Sergeant-Major of the 48th Highlanders of Canada. Small and his fellow Canadian soldiers stood by helplessly in Britain while Germany’s Blitzkrieg rolled over the British and Western European allies in France and the Low Countries in May and June of 1940. The men were elated when they received orders to proceed to France. Small’s 48th Highlanders of Canada were inspected by King George VI and then moved from Camp Aldershot to the embarkation point at Plymouth. On the way, they found out that the 51st Highland Division (which contained their allied regiment, the Gordon Highlanders) had just been encircled and destroyed near St Valéry, France. With happy memories of last winter’s snowball fights with the Gordons still fresh in their minds, the gravity of their situation must have started to sink in.

Let us look to his diary.

11 June 1940 1p.m. entrained for Plymouth. Stayed under canvas – sailed on Ville D’Alger – shores of Plymouth packed with people. Wonderful send off – 2 troopships & good escort. First Canadians to land in France.

Small’s journey begins on a “scruffy French channel craft”, the Ville d’Alger. It appears he was a member of the battalion’s Transport Section, which along with the (Bren Gun) Carrier Section led the way to the continent ahead of their regiment’s main body.

12 June 1940 Landed at Brest at 10a.m. – good trip. Looked the town over – got paid (French Francs).

Small’s advance party landed in France. It must have been an emotional feeling for him, as Small had fought in France as a 17-year-old rifleman with the 19th Battalion during Canada’s Hundred Days Offensive of 1918. There would be little fanfare however. Upon arrival the men found a “dismaying atmosphere” at Brest. There was no official welcome. French soldiers indifferently lounged around while civilian refugees carrying all they could crammed the streets. Small went to work unloading his section’s trucks and motorcycles in the busy port. It would be exhausting non-stop work as thousands of men, vehicles and equipment would be disembarking behind them.

13 June 1940 Left Brest about 1p.m. after unloading transport – slept in bush at Mur-de-Bretagne – tired out

Small’s party set off toward the planned Rennes-Laval-Le Mans assembly area (headquarters being established at the city of Le Mans). The 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade’s Carrier and Transport Sections took the roads, while the main force traveled by rail. The route was clogged with refugees, whom local authorities had given the right-of-way, causing the convoys to move fitfully. At the end of the day Small would camp at Mûr-De-Bretagne, having moved 130km inland from Brest.

14 June 1940 Started on road again – rode all day – stopped in bush for the night at Bouessay. Havent seen the Regt. yet,

After a long day’s drive, Small would camp at the small town of Bouessay, outside of Sablé-sur-Sarthe, now about 360km inland from Brest, and 60km from Le Mans.

While on the road, the situation had changed drastically – that morning German troops reached Paris, and to save the historic city from destruction, the French would not defend it. German soldiers marched down the Champs Elysées under a swastika-covered Arc de Triomphe. They would not stop for long. The French armies were now cut off from each other and unable to put up a coherent defence.

The British War Office, fearing total collapse in France, issued orders to recall the BEF. They would be needed for the next battleground – Britain.

15 June 1940 4:30a.m. British Retiring – also us. Got back as far as Landesvous(?). Walking in circles – what a life! Still haven’t found the Regt.

In the confusion, the 48th‘s Transport and Carrier Sections were not able to rendezvous with the main force. They began their withdrawal to the port among fears of aerial attack and rumours of a sweeping German advance.

Small’s party managed to drive 325km to the town of Landivisiau, about 40km outside of Brest.

“None of us will forget that drive. We passed thousands of refugees, in fact most of the roads were choked with them, poor devils. I don’t know where they wanted to go; anywhere away from the Germans, I supposed. They were all ages, and all were carrying bundles… The only greetings we received now were black scowls…” – Basil Smith, Transport Sergeant, Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment. Part of the same brigade, the “Hasty P’s” Carrier and Transport Sections also came to France on the Ville d’Alger, and would have traveled in conjunction with Small’s party.

16 June 1940 Took up positions in bush outside Londesvous(?). Extra ammunition. Hiley(?) shot through hand – Resneven(?)

Things are becoming chaotic. An edgy night was spent in defensive positions, on high alert for attacks from the air or by land. The man shot would have been from friendly fire or a negligent discharge, for the German army, unbeknownst to the men, were still hundreds of kilometres away.

Small’s section was now paused at the town of Lesneven, outside of Brest. That afternoon, a German reconnaissance plane appeared over the port at Brest – flying low and observing the withdrawing Allied forces. Canadians on board the Canterbury Belle let loose with their deck-mounted Bren Guns, joined almost instantly with “every rifle, pistol, anti-tank rifle, or other weapon upon which three thousand men could lay their hands on” [Mowat]. The plane retreated, smoke trailing from one engine.

Any secrecy the men thought they may have had was now gone.

17 June 1940 Ordered to wreck transport – took 4 trucks & Bren Guns, bombs & ammunition (?). On Brigitte at Brest – 4:30p.m.

Basil Smith continued: “We arrived on the outskirts of Brest … and there must have been a solid mile of British vehicles ahead of us, bumper to bumper. We joined them, and in a little while there was a mile of them behind us too. What the Luftwaffe was doing on that day I’ll never know, but we sure expected the same treatment the boys got at Dunkirk.”

Vehicle convoys were arranged in makeshift parking lots on the outskirts of the town, and it appears the Carrier and Transport Sections were now split up as they awaited space on ships. Small and his party settled in and waited. According to Smith it was “some of the most nervous hours I can recall. The tension was worse than being under shell-fire later in the war. We were momentarily expecting a Panzer column to come sweeping down the road.”

Their fears were valid. A week ago the entire 51st Highland Division had been wiped out at St Valery before they could evacuate, by Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division.

The 7th Panzer Division had now turned their attention to Cherbourg, where other components of the Second BEF were now evacuating (as it was not practical for all units to go back to Brest – others went to St Malo). The Germans penetrated to within 3 miles of Cherbourg’s harbour as the last Allied troopship left there.

At Brest the enemy was not actually in the vicinity, but anxious British authorities at the port ordered the Canadians to destroy their vehicles and other equipment. They wanted to evacuate as many men as possible, as quickly as possible, and the hardware took up too much space. Lest it fall into enemy hands, they were ordered to destroy their equipment by fire.

Upon receiving the order, a disappointed Small went to work wrecking his lorries which he had shepherded through France. Once again Basil Smith’s account shows how this was done: “we couldn’t burn the trucks because it would have […] drawn every German plane for a hundred miles, so we did the next best. We went to work on all those lovely new trucks with pickaxes; punctured the tires, gas tanks and radiators; jammed up the bodies, sheared off engine parts and cracked the blocks. Then we destroyed the equipment in them…”

By late afternoon Small’s party had found space on a ship bound for England.

18 June 1940 Landed at Plymouth at 7a.m. – off boat 6p.m. Slept on Swan Pool Beach all night.

The Brigitte carried the men “back to England in style” as the Transport Officer, Lieutenant Don MacKenzie put it. It was “a crowded little pleasure launch which would have looked home on Toronto Bay.”

After stopping at Plymouth, where the main force was disembarking, the Brigitte continued on to Falmouth (about 90 minutes away by road) for reasons unknown.

An exhausted Small disembarked and then slept on Swanpool Beach.

He still had not seen the rest of the Regiment.

19 June 1940 Left beach & left Falmouth for Aldershot. Arrived at 8:30p.m. – dead tired.

As it happened, the scattered sub-units of the 48th Highlanders had all returned to the Canadian Camp at Aldershot by June 18th, save for the Transport Section. Worry grew among the regiment, and the outstanding men’s names were being entered into a list titled “The following are SOS, missing believed prisoner’s of war” to be published in Orders. When Small and his party returned arrived late on the 19th, they were “greeted like men escaped from a prisoners’ cage”.

The dead tired Small would have little time to rest. As Winston Churchill put it the day before in a rousing speech: “The Battle of France is over. The Battle of Britain is about to begin.”

Postscript

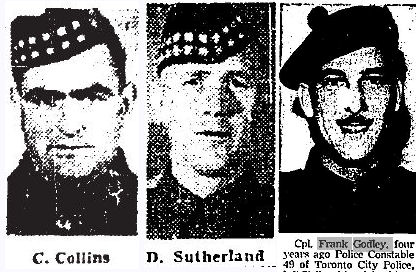

Small would learn of the journey of the main force of the 48th Highlanders who had traveled by rail. They had been in the lead train with Brigade Headquarters. This group likely included other Toronto policemen who had joined the 48th in the early days of the war. Constable Frank Godley (49), was now serving as a Sergeant in the Battalion HQ. Also with the 48th were Constables “Army” Armstrong (9), Clarence Collins (332), William McMillan (237), and David Sutherland (507). The 48th train penetrated the furthest of any Canadians, reaching Sablé-sur-Sarthe. Once there they received the order to reverse from a British Railway Transport Officer (RTO). The seemingly nervous RTO insisted they flee but could not produce the order to do so nor his credentials. The Canadians thought he was a German Agent and quizzed him on his name, “Oates”. A man of the same name was famous at the time as a member of Scott’s Antarctic Expedition of 1910-13. The RTO knew enough about this bit of trivia to pass as a true Brit and the Canadians were satisfied the order was genuine.

However they now had an issue with the trains French engineer. “Finie la guerre!” he cried, refusing to move his train in the opposite direction. He happened to live in Sablé and wanted to go home. He became irate and would only comply at gunpoint. The trains crew had mostly managed to leave. Luckily, Platoon Sergeant-Major Jack Laurie had been a railwayman before the war and said he could run the train back, and pressed other soldiers into service as stokers. The men posted Bren gunners at the doors, smashed out windows to reduce potential shrapnel, and placed an AA gun on a flatbed car. “The entire battalion was aboard, crowded at the windows and staring at the early sky, nervously watching for Stukas”. Before setting off the “recalcitrant engineer” again tried to get off the train, supposedly to have breakfast. “Someone tell the goddamn Frog he’ll eat here or else!” Laurie shouted.

The train then took off for Brest with a “defiant little toot” of its horn. But at some point in the journey, the French engineer outwitted the Canadians and switched course for St Malo, a port closer to his home. When the 48th arrived at the harbour, there was just one ship left with orders to evacuate British troops, the SS Biarritz. It was already loaded but stuck in low tide. Room was made aboard for the Canadians and they spent a long night waiting for the tide to come in. “Enemy air attack was expected all night long; several other French ports were being heavily bombed, and there was no reason why St. Malo should be immune, but the night passed undisturbed.”

The Biarritz carried them off just as Royal Navy demolition parties blew the outer locks. France would surrender days later.

For their part in the Battle of France, Canadians were awarded the 1939-1945 Star. It would be years before they would return to French soil. All in all, the men acquitted themselves well in the chaotic campaign. Though 216 vehicles and much equipment were lost, Canada’s human losses for the operation were incredibly light, with only 1 killed, and 5 missing – taken prisoner. The fatality was due to a motorcycle collision on the frenzied roads; and of the 5 men captured only one would remain a prisoner at the end of the war – the other four escaping back to England (notably, one of the escapees would account for the war’s first Military Medal awarded to a member of the Canadian Army).

The 1st Canadian Division’s ability to make it back to Britain almost entirely intact (minus the scrapped equipment) was necessary for any planned defence of the British Isles.

They would soon be under attack from the air, and Small’s diary again provides a glimpse into that time. To be continued…

Sources and further reading:

- J. Sarjeant. The Secrets in the Chest: The Life of James Edward “Tiny” Small. Rose Printing, Orillia. 2016.

- K. Beattie. Dileas. History of the 48th Highlanders of Canada 1929-1956. The 48th Highlanders of Canada, Toronto. 1957.

- F. Mowat. The Regiment. Dundurn, Toronto. 1955.

- T. Copp. Legion Magazine – The Fall of France Part 2. October 1995.

- C.P. Stacey. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Vol. I Six Years of War. Queen’s Printer for Canada, Ottawa. 1955.

- D.C. Draper. Annual Report of the Chief Constable of the City of Toronto for the Year 1940. Toronto, 1941.

A note on quotations: Diary entries are duplicated from Sarjeant’s “The Secrets in the Chest” with permission from the author. All uncredited quotations are taken from Beattie’s “Dileas”, except for Basil Smith’s account, which appears from Mowat’s “The Regiment”.