The Influence of Military Veterans in the Early Toronto Police Force

Victorian-Era Toronto was a town filled with affluent merchants, colleges and universities, cathedrals and parks. It was also home to more unpleasant by-products of the industrial age – slums and poverty. Religious divisions inherited from the British Isles added to instability and civil disorder and riots were a common occurrence. A modern, professional police force was required to meet the challenges of public safety in this environment. Military veterans were instrumental in the formative years of the Toronto Police Service.

The Early Chiefs and the Road to Reform

When York, Upper Canada was incorporated as the City of Toronto in 1834, the town’s high bailiff, William Higgins, became the first (and only) constable in the city. The following year, Higgins was replaced and the Toronto Police expanded to have five constables serving under a High Constable – George Kingsmill. Kingsmill, a native Irishman, had been a commissioned officer of the British Army, and is therefore the first known military veteran in the ranks of the Toronto Police.

(Toronto Public Library – Digital Archive)

In early years, the Toronto Police Force modelled itself mainly on the Metropolitan Police of London, England, whose police practices drew inspiration from Sir Robert Peel. The British politician now known for the “Peelian Principles” laid the groundwork to create modern civilian policing, which separated the military from law enforcement duties, which had previously been common. His axioms of community policing are irrefutable and still held in high regard today, but they do not mean that military characteristics should be completely done away with from police organizations.

Unfortunately, in practice those high-minded principles did not trickle down to the early Toronto Police Force. The city was tense and divided along religious lines between the majority Protestant and minority Catholic denominations in the city. This frequently led to violence, with police often joining in. High Constable Kingsmill proved to be strongly partisan. New Toronto constables were handpicked by local politicians. Many showed obvious bias while performing their duties. By 1859 there were so many sectarian scandals in the Toronto Police (such as participating in the 1855 Toronto Circus Riot), that a Board of Commissioners was created and its first act was to sack the entire force along with then-Chief Samuel Sherwood. To curb the nepotism, the men were replaced by new constables recruited externally, mostly from the British Isles.

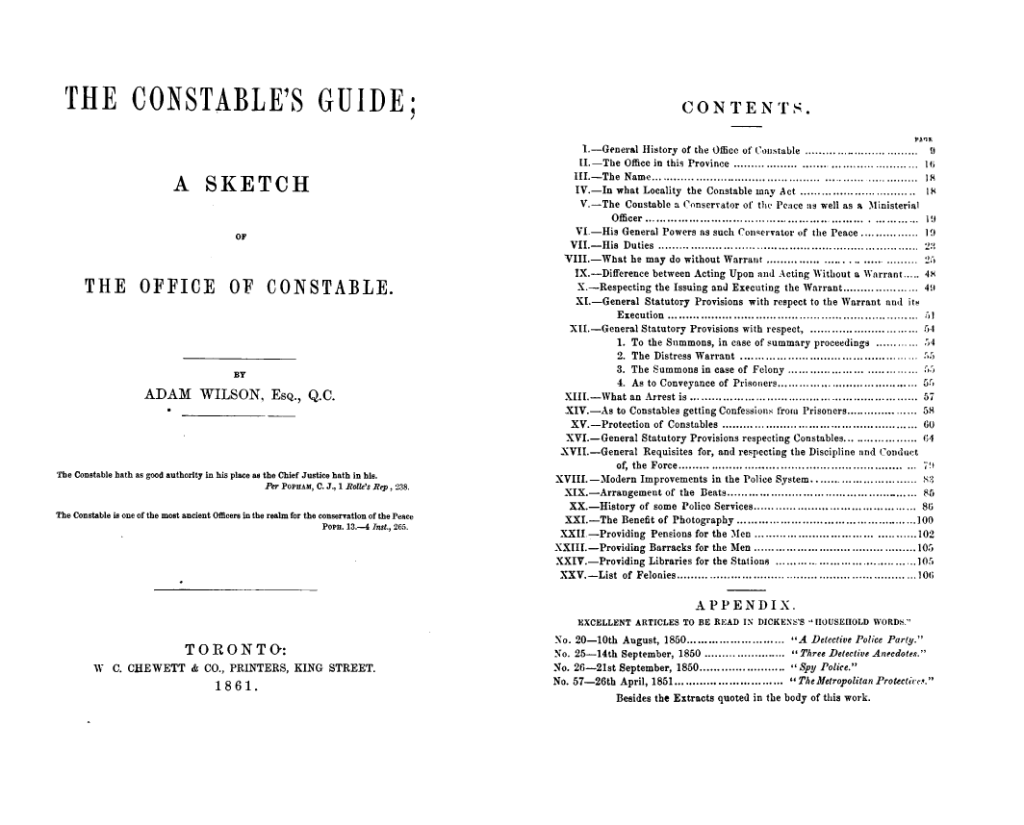

More importantly, the new Chief Constable was also chosen from abroad. Instead of selecting another senior police officer, civic leaders chose William Stratton Prince, a former army Captain of the 71st Highland Light Infantry. They thought a military officer would be better able to control the men and change course. Among reforms was the 1859 Constable’s Guide, which Prince would strictly enforce, bolstered by his subsequent “Orders Books”. These publications, similar to an army regiment’s Standing Orders, laid out the standards, rules and regulations members must adhere to. In them, Peel’s principles would be protected. For example, it limited the use of force: “In the arrest of criminals and disorderly characters, drunkards, especially the latter, men are cautioned against the unnecessary use of the baton when persuasion and a little patience on the part of the policeman would suppress all violence on the part of those arrested.”

Aside from a recruiting preference for Britons, the Toronto Police Force began hiring more military veterans into its ranks. Having seasoned soldiers bolstering the ranks ensured that police personnel were fit for the challenge of reform as it was predicted that their self-discipline and hardiness would rub off on other members of the force. The 1860 nominal roll shows 14 of 49 constables were ex-servicemen, making up more than a quarter of the force. A further 12 had served in the paramilitary Irish Constabulary (later the Royal Irish Constabulary).

The life of a Victorian Era constable was difficult. Expectations were now higher than ever. With a network of “beats” crisscrossing Toronto, officers fanned out from their stations daily on long foot patrols. They would patrol everything from bustling city streets to the rural outskirts of town. They walked their beats alone day into night, year-round and in all weather conditions. Constables were expected to be ready for everything and uphold the law oftentimes without rapid backup. Prince ensured beats were strictly timed and Patrol Sergeants made regular field inspections to ensure the rules, regulations and standards were being adhered to. Employing military veterans ensured the Force was physically and mentally up to the task. As one reporter from The Globe newspaper later observed: “the number of old soldiers in the corps seemed to infuse their military blood into their less confident confrères”.

The Chief appointed one such Constable, William Ward (late Coldstream Guards, British Army) to be a Drill Instructor for the Force to drill the men regularly Chief Prince saw the value in the “Three D’s” – Drill, Dress and Deportment common to the military.

Drill, the co-ordinated movements used by militaries since antiquity, formed bonds in the men and reinforced the idea of acting as a team and swiftly following orders. Dress, the correct way to wear a uniform, is key in being easily identifiable and looking competent. Deportment, how one carries themselves, aids in being received as competent and professional.

With a former Guardsman teaching the men these “Three D’s”, there would be a significant culture change. This was a necessary change, as the members of the force prior to the 1859 reforms had been described as being “without uniformity, except in one respect—they were uniformly slovenly”. It was also said that those men “might say as to their boots what was generally said to wagons and carriages, that if the mud was taken off they would be just as dirty in a short time again.” This of course was partly due to the fact that then-Chief Sherwood had been seen as soft – “a quiet, good-natured man,” who “did not insist on any strict regulations as to the dress or discipline of the men.”1

Prince placed such importance on Drill that he went so far as to include his expectations of it in Order Book 1861-1862 , such as his instructions for the position of “Attention”:

The heels must be in a line and closed — the knees straight — the toes turned out so that the feet may form an angle of 60 degrees — the arms hanging straight down for the shoulders — the elbows turned in and close to the sides — the thumb kept close to the forefinger — the Head to be bent and in giving evidence the body, arms and hands to be perfectly steady — in fact — exactly the same position as a soldier in the Ranks or parade addressing his Officer.

Prince further required officers stand at attention while in the presence of superiors, and whenever addressing the Bench while testifying in court. According to police historian the late Superintendent Jack Webster, testifying at attention was a tradition which continued at least into the 1950’s.

More than just looking good however, the Three D’s have an officer safety benefit. To this day in Ontario, police officers are taught that “Officer Presence” is the first step in de-escalation. According to the Ontario Police College, studies show that if an offender views an officer as competent, the offender is less likely to attempt violence during a police encounter. Similarly, if a member of the public views an officer as competent, they are more agreeable to an officer’s lawful authority, reducing conflict.

As the Force became skilled at Drill through weekly practice, Prince introduced “extension drill” and “revolver drill” – infantry-style movements of massed policemen conducting fire and manoeuvre. It should be remembered that at the time, Southern Ontario and other parts of Canada were periodically invaded by Fenian rebels in a bid to overthrow the Canadian Government.

The “Blue Coats” into the 20th Century

After 15 years of service, Prince gave way to a new Chief, Francis Collier Draper in 1874. Local government opted to again choose a military veteran to helm the Toronto Police Force. Draper had been a Major in the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada.

One of Draper’s innovations was the creation of a Mounted Police unit, in 1886. These horse-mounted officers could patrol the city’s more rural areas, as well as for “escort duty during the passing of processions through the streets and the recapture of prisoners who may occasionally effect their escape from Gaol or the Central Prison,” as noted in his Annual Report. Draper would select a small corps of constables with military backgrounds to pioneer the unit, such as PC George Watson who had 12 years service with the Royal Horse Artillery, as well as Sergeant Charles Seymour and Constable George Goulding who had 10 years and 4 and a half years under Her Majesty’s Service respectively. The Mounted Unit proved extremely useful in crowd management and community policing and survives to this day.

Draper continued the emphasis on drill, and annual inspections of the Force were held publicly, reviewed by dignitaries and watched by enthusiastic spectators. He also emphasized skill-at-arms and ended inspections with revolver displays and the awarding of prizes. This improved officers’ firearms proficiency and safe weapons handling, which in turn enhanced both officer and public safety. Draper’s annual reports to the mayor included subsections on Drill, Discipline and Pistol Practice to monitor the men’s progress.

Closing out the 19th Century, another accomplished military officer was selected to take over the professionalized force – Chief Constable Henry James Grasett.

Born to the rector of St. James Cathedral in Toronto, a young Henry Grasett joined the Canadian Militia as a Rifleman in the 2nd Battalion, Volunteer Militia Rifles of Toronto, also known as the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada. He would fight at Canada’s earliest modern battle – the Battle of Ridgeway near Fort Erie, Ontario, during the 1866 Fenian Raids. The 19-year-old Grasett’s regiment would sustain the highest casualties of the day in the face of sustained Fenian musket volleys. While the Canadians lost the battle, the Irish-American rebels ultimately fled back to the United States. Afterwards, Grasett entered imperial service, commissioning as an officer with the British Army’s 100th Regiment of Foot (Prince of Wales’ Royal Canadians). Completing his term in England, he would return to Toronto as Commanding Officer of the 10th Battalion, Royal Grenadiers, today The Royal Regiment of Canada. Grasett would again see combat during the 1885 Northwest Rebellion. After leading his men on a cold and grueling overland expedition from Toronto to Saskatchewan, Grasett would successfully command his troops in battle, facing down the Métis rifle pits at Fish Creek and Batoche, helping to end Riel’s Rebellion.

Returning to the city with praise, Grasett was appointed Chief Constable of Toronto in December 1886. He would serve 34 years in office, becoming Toronto’s longest serving police chief. Grasett continued the practice of hiring military veterans into the ranks, recognizing that this policy had favourable results. It also provided stability in the rapidly growing department. Grasett inherited a 174 member force, which would grow to 265 in just three years, and 300 by the end of the century.

Grassett, like his predecessors, expected strict adherence to procedure, and in 1890 released a 121-page revision of the Constable’s Guide titled Rules and Regulations of the Toronto Police Force. Dissidents would face court-martial style discipline.

The old soldier also kept up the annual inspections of the Force, and he continued to evolve the skirmishing drills started by Prince. Following the march-past in the 1889 Annual Inspection, The Globe reported: “After again extending into the line, the Battalion was drawn up for revolver-firing exercises […] with the front rank kneeling and the second standing. There was a pardonable gleam of pride on the face of Chief Grasett as he stood in front of his soldier-policemen as they fired volleys of blank cartridges. It would be a rough experience for a mob to stand in front of such a line of magnificent fellows and defy the authority of the law. Volley-firing by companies and then individual firing by the men completed that part of the display.” The reviewing party was “frequent in their praise of the admirable discipline of the force.”

While this may seem like an escalation in force, it actually served to reduce dependence on using the military to “Aid the Civil Power” when municipalities couldn’t cope with an emergency. Due to the upheaval caused by industrialization, the Canadian Militia had been called out to several disturbances of the peace in the late 19th century, causing soldiers to face off with citizens. One such disturbance, the 1877 Belleville Riots, required the military to enforce the peace. In the scuffle, troops from Toronto’s Queen’s Own Rifles were swarmed, pelted with projectiles and injured. In return, rioters were also hurt, with at least one rioter received a sword wound.2

These new police tactics were merely a deterrent however, and it should be noted that volley-firing by police lines would never actually occur on the streets of Toronto. Relying on community police instead of soldiers to keep the peace under all circumstances has become a cornerstone of our democracy, and these rudimentary tactics were the beginnings of this independence from martial law.

One final militaristic addition to the force in this period, would be the introduction of group physical training (or “PT”) in 1898. The force’s Chief surgeon, Dr. Edward Spragge, spoke of the obvious benefits in that years Annual Report: “introduction of the gymnastic exercises cannot fail to produce improved condition of the men, and consequently of their general health.”

By the end of the Victorian Era, Toronto’s police service had come a long way, from un-uniformed, partisan and undisciplined officers to orderly, regulated and meticulous officers dedicated to principled policing and the rule of law. This was achieved through the influence of military men joining the police department and infusing the positive elements of military axioms into the force, all while keeping with Peel’s Principles. Their establishment of standing orders, rules and regulations to codify progressive police practices, and developing high standards of drill, dress and deportment had greatly improved the force and benefited the citizens of Toronto for generations.

Postscript: Drill Instructor William Ward

In 1864, a newly appointed constable and military veteran, William Ward, would be the main driver of Chief Prince’s reforms of the force and shaped its culture for the rest of the century.

Born in Devonshire, England in 1837, Ward enlisted in the British Army in his teenage years. Briefly serving in the territorial militia, Ward went on to join the Coldstream Guards. World-famous for their bearskin hats and red tunics, the Coldstreams have guarded the Sovereign for centuries and still mount the King’s Guard at Buckingham Palace today.

Around 1855, the now 18-year-old Ward was posted to the regiment’s 2nd Battalion in London. Six months later, he was called to active service in the Crimean War – where Britain and her Allies were fighting a war over that Black Sea peninsula against an expansionist Imperial Russia. Arriving as a replacement after his unit’s heavy fighting at Inkerman, he would serve with them throughout the Siege of Sebastopol. The siege is considered one of the last classic sieges in history, and one of the first instances of modern trench warfare. The year long-siege involved tens of thousands of men, and culminated in fierce attacks on entrenched Russian positions. Ward’s Guards Brigade endured miserable conditions and heavy losses – 425 killed in action and four times that number died of illness. Their eventual success at Sebastopol won the war.

The unit, known for their excellence as the Queen’s body guard, shocked Queen Victoria when the returned men paraded in front of her, a parade in which Ward is known to have taken part. Her Majesty remarked afterwards that the men on parade seemed ‘quite broken down’ since she had last seen them3.

As a mark of his admirable conduct as a soldier, Ward was chosen as a member of the 40-man honour guard who received the allied Napoleon III on the Isle of Wight during the French leader’s state visit of 1857. Ward continued climbing the ranks, to Sergeant. In 1861, when the American Civil War caused a military crisis in Canada, the veteran Guardsman answered the call for seasoned British Army regulars to train the Canadian Militia. He trained units all over Southern Ontario for three years – troops that would later face the invading Fenian rebels.

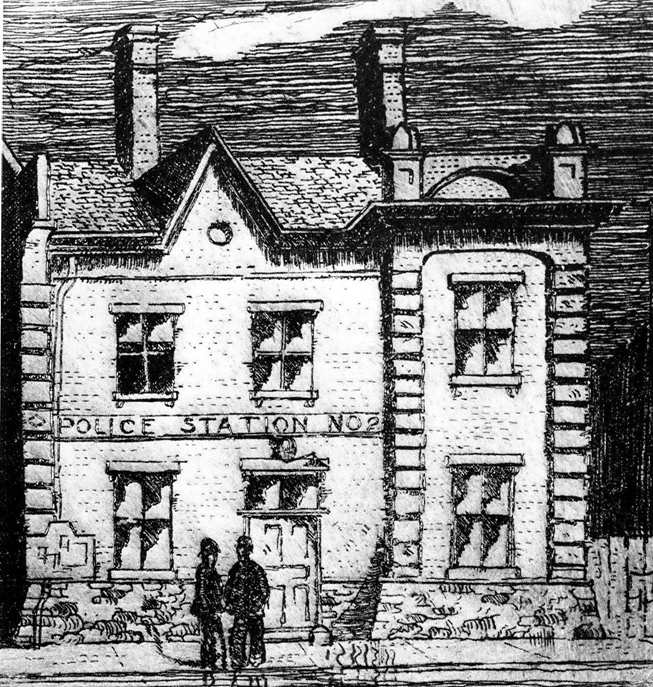

With the end of his military service approaching, Ward decided to make the new country his home. To this end, he joined the Toronto Police Force at the end of 1864. Ward was posted to the scrappy No. 2 Division downtown. There, he would learn his new trade while walking the beat in St John’s Ward, a slum near present-day Old City Hall described at the time as a place “looken upon as the most notorious part of Toronto”.

Due to Ward’s impeccable credentials, Chief Prince saw to it that he was “immediately placed in the capacity of drill instructor,” where he would begin instilling his high standards of the Drill, Dress and Deportment into the Toronto Police Force.

Ward would begin drilling his fellow policemen to a Guardsman’s standards. His leadership abilities saw him promoted to Patrol Sergeant in just two short years. In 1871, Ward was again promoted to Senior Sergeant, and in 1876 promoted again to Sergeant-Major – a rank which was restructured to Inspector in 1878.

Despite his advancement and added responsibility, Ward still found extra time to instruct drill classes. These were held weekly on Thursdays from April to September at Queen’s Park, where, coincidentally, two Russian cannons captured at the Siege of Sebastopol overlooked the entrance to the park. Gifted by Queen Victoria in recognition of the Canadians who fought there, they still stand in the park (though since moved to in front of the legislature).

One witness described a typical scene of the constables drilling in the park: “Inspector Ward took command, and exercised the men in marching, extension drill, and revolver drill. The precision with which they executed the various movements in marching” drew praise from the Chief, who credited both the men themselves and their instructor.

The classes were held in anticipation of Annual Inspections of the Force4.

On 28 August 1879, while the rest of the force was on duty 84 officers gathered on parade, boots polished, buttons and handcuffs gleaming. With the Band of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada leading, the contingent marched a spectator-lined route from the Armoury at the foot of Jarvis Street to the Cricket Grounds in the Annex. Once there, Chief Draper commenced his annual inspection of the Force. Mayor James Beaty commended the officers present for their discipline, expressing his belief that in this regard, “the Force was unequalled on this continent.” Lieutenant Governor William Ross MacDonald acknowledged the advancements the force had made in the last twenty years, remarking that the men had “discharged their duty faithfully, conducted themselves creditably” and that they should strive to maintain “the good reputation which they have won”. Ward’s efforts over the past fifteen years had bore fruit.

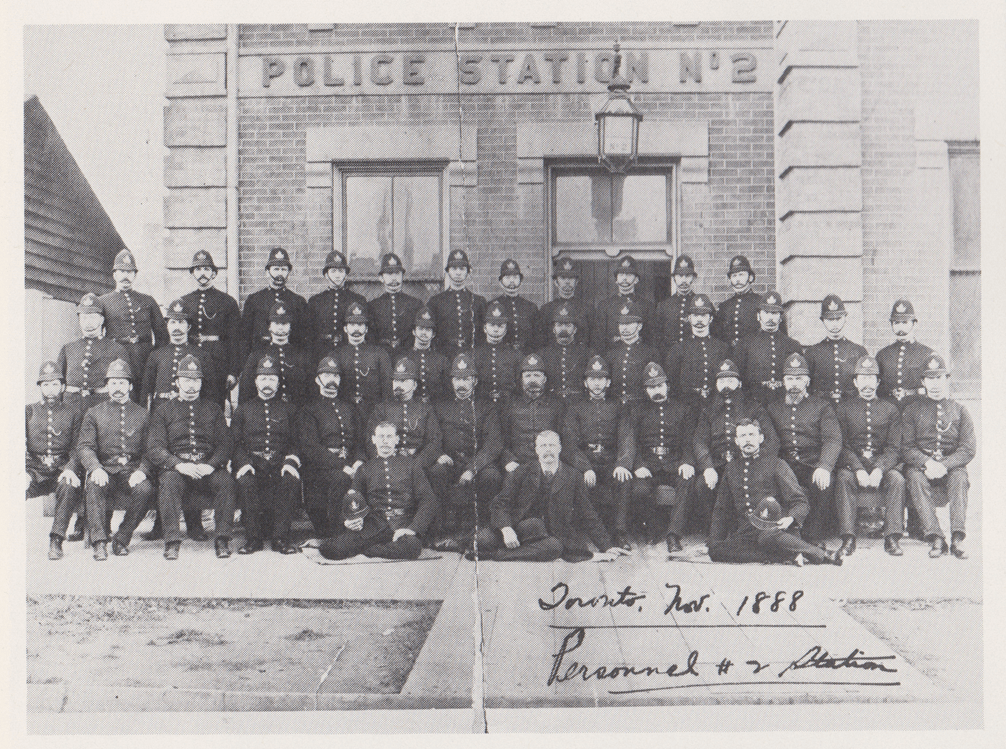

The progress continued as the Force grew. A decade later, 220 members of the Force gathered on parade for the 1889 Annual Inspection. Inspector Ward led a company of his men from No. 2 Station on a march past and review by Sir Adolphe Caron, the Minister of Militia and Defence, and local dignitaries. The parade was a success and the following day, a reporter beamed “…to the strains of the ‘British Grenadiers’ the six companies marched past the saluting point. The movement of the men was of wonderful steadiness, and would have reflected credit on even the best drilled companies of the crack city regiments.”

Aside from his managerial and instructional duties, the old soldier continued to share the risks of his men, and led from the front. “During his fifteen-years inspectorship he was called upon to encounter many dangers, but he was never known to ask his men to undertake perilous duty without being in the lead.” During the 1875 Pilgrimage Procession Riots, notable for the police being fired upon, Ward and his “small section of twenty men stood bravely between the passionate crowds, and although they were bruised and beaten succeeded in preventing bloodshed”5. In another example from 1890, Ward was again leading a line of police during sectarian rioting where the Inspector was “struck on the head by a well-aimed missile” receiving a severe scalp wound6.

In 1891, Inspector Ward retired after many years serving at No 2 Station, took up farming in Calgary with his sons. By the time of his retirement, the 40-member Toronto Police Force he had joined had grown exponentially to 300 men – “every one of whom have passed under the drill instruction of Inspector Ward,” noted The Globe.

Sources and Further Reading

- A. Wilson – A Constable’s Guide; A Sketch of the Office of Constable. W.C. Chewett & Co., Printers; Toronto, 1859.

- Toronto Police Force – Toronto Police Force: A Brief Account of the Force Since Its Re-Organization In 1859 Up To The Present Date. E. F. Clarke, Printer; Toronto, 1886.

- [1] C.C. Taylor. The Queen’s Jubilee and Toronto “Called Back” From 1887 to 1847. William Briggs, Printer; Toronto, 1887.

- H.J. Grassett. Rules and Regulations of the Toronto Police Force. Finish

- F. C. Draper – Annual Report of the Chief Constable of the City of Toronto For the Year[s] 1879; 1881; 1884; 1885.

- H. J. Grassett – Annual Report of the Chief Constable of the City of Toronto For the Year[s] 1886; 1887; 1889.

- D. A. Brock – Metropolitan Toronto Police: To Serve and Protect, Volume I. D. W. Friesen and Sons Ltd; Altona, 1979.

- B. Wardle – The Mounted Squad : An Illustrated History of the Toronto Mounted Police 1886-2000. Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd; Markham 2002.

- [2] W. T. Barnard. The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, 1860-1960: One Hundred Years of Canada. Ontario Publishing Company; Toronto, 1960. pp.41-43

- D. J. Goodspeed. Battle Royal: A History of the The Royal Regiment of Canada 1862-1962. The Royal Regiment of Canada Association; Toronto 1962.

- D. Ross & G. Tyler. Canadian Campaigns 1860-70. Osprey Publishing Ltd.; Long Island City, 2005.

- J. Webster. Copper Jack: My Life on the Force. Dundurn Press; Toronto 1991.

- City of Toronto Archives – Journals of the Common Council of the City of Toronto. Fonds 200, Series 1080.

- Minutes of Proceedings for the Council Corporation of the City of Toronto, 1863.

- Minutes of Proceedings for the Council Corporation of the City of Toronto 1866.

- Toronto Public Library. Historical Newspaper Database.

- The Globe. 1879-08-29 “Toronto Police Force – Annual Inspection Yesterday on the Cricket Ground,” Page 4.

- The Globe. 1881-07-16 “Policemen at Drill,” Page 14.

- [1]The Globe. 1882-08-11 “The Finest In The World,” Page 9.

- [4]The Globe. 1883-04-28 “The Police Drill,” Page 14.

- The Globe. 1886-10-13 “The Police Force,” Page 9.

- The Globe. 1889-11-11 “The Blue Coats,” Page 4.

- [6]The Globe. 1890-08-07 “Policeman’s Baton,” Page 4.

- [5]The Globe. 1891-05-16 “Inspector William Ward,” Page 2.

- P. Vronsky – History of the Toronto Police in the 19th Century, History of Policing in Toronto. [http://www.petervronsky.org/crime/cp0.htm] Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- G. Marquis – GRASETT, HENRY JAMES (1847-1930), Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15. University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003.[http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grasett_henry_james_1847_1930_15E.html] Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- [3]The Guards Museum – The Crimean War 1854-1856, History of the Foot Guards. [https://theguardsmuseum.com/about-the-guards/history-of-the-foot-guards/crimean-war-1854-1856/] Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- A. Bunch. Spacing Toronto. The Toronto Circus Riot of 1855: The Day the Clowns Picked the Wrong Toronto Brothel. [http://spacing.ca/toronto/2012/10/02/the-toronto-circus-riot-of-1855-the-day-the-clowns-picked-the-wrong-toronto-brothel/] Retrieved 25 October 2022.