The links between Toronto Police and Toronto Artillery

Note: The following is a prepared speech from Matthew Scarlino, Historian – Toronto Police Military Veterans Association on occasion of a charitable donation to the Toronto Artillery Foundation, 9 May 2022. Unfortunately, a COVID-19 infection kept the author from delivering the speech, though it was ably presented by Lt. Col. (Ret’d) Dana Gidlow, CD.

Good evening distinguished guests, Ladies and Gentlemen.

The intertwined history of the Toronto Artillery and the Toronto Police is a rich one. Forged over a century, including two world wars, other conflicts and domestic service, our two organizations have shared members and values for a long time.

I’m going to speak to our closeness by looking at our service in conflict and key individuals that unite our organizations and our associations.

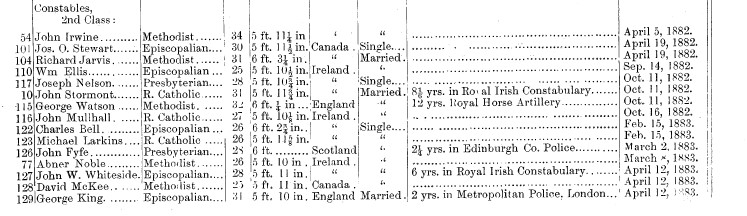

Gunners have served in the Toronto Police from the earliest days. A look at our Nominal Roll from 1886 shows that our Deputy Chief, William Stewart, was himself an artillery veteran. As for the regular beat constables, the nominal rolls simply marked prior military service as being with the “Canadian Volunteers”. Undoubtedly, there were gunners among them.

One key figure was Constable George Watson, who had served twelve years in the Royal Horse Artillery. PC Watson was an important figure in the foundation of the Toronto Police Mounted Unit, that same year. Selected for his police talents and his expertise riding the tough draft horses of the RHA, he was promoted to Sergeant and was instrumental in the early success of the Mounted Unit, which continues to serve the citizens of Toronto to this day.

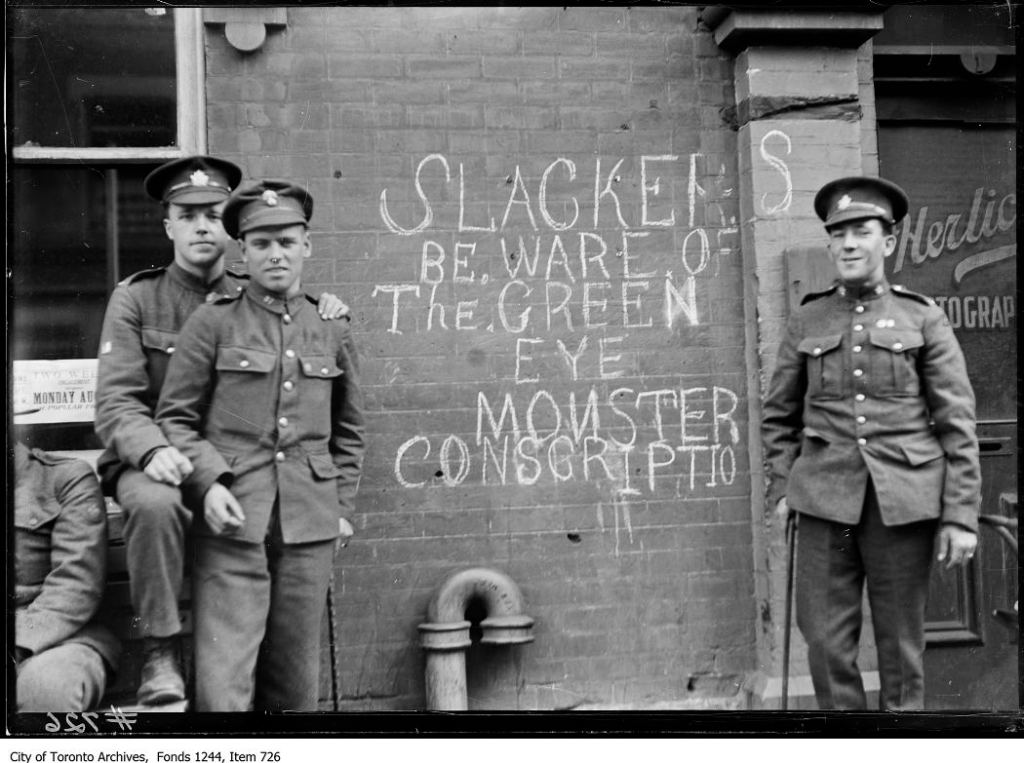

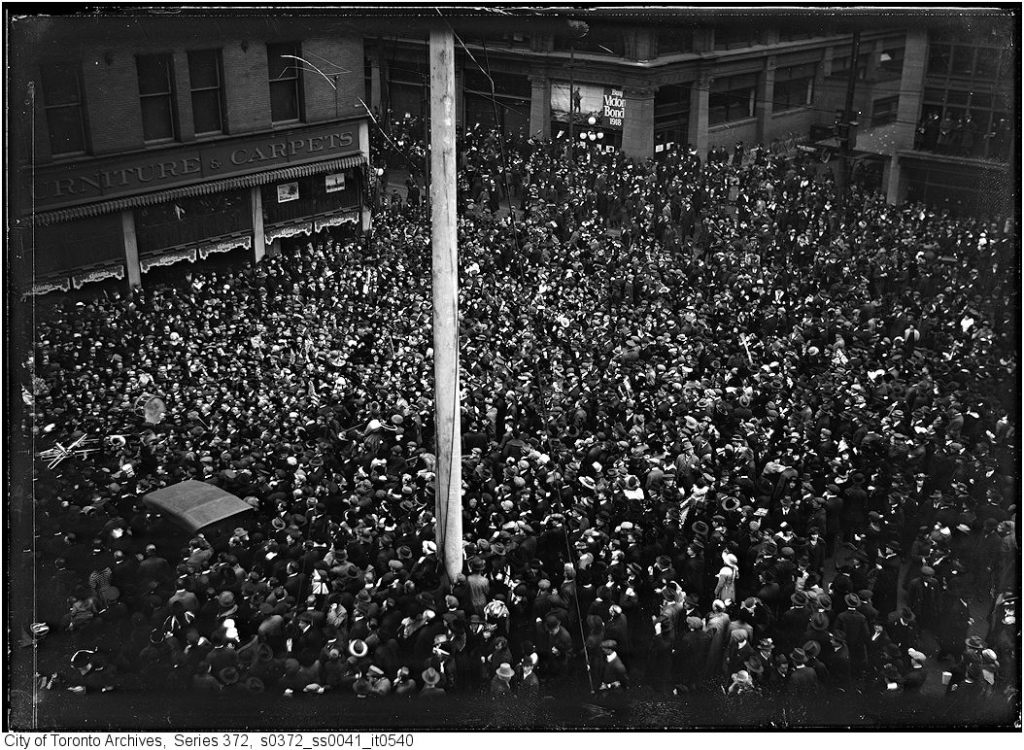

It was during the First War that our two organizations really forged their bonds. The guns still being horse-driven, four mounted policemen joined Toronto’s 9th Battery when the war broke out in the autumn of 1914. They escorted the police force’s donation of 19 police horses to the Battery.

Of our men in 9 Battery, there was:

Constable Thomas Hugh Dundas, atop police horse Bunny, who rose to the rank of Battery Sergeant-Major. He would be wounded repeatedly and was the most decorated Toronto Police officer serving in the First World War. He won the Military Medal, the Meritorious Service Medal, and was Mentioned-in-Despatches.

Constable Ernest Masters, was commissioned from the ranks due to bravery in the field.

And Constable Charlie Chalkin, atop police-horse Mischief, served in the battery until halfway through the war, when he served as a Mounted military policeman patrolling the streets of France, no doubt keeping gunners out of trouble.

Constable William Connor, atop police-horse Charlie, served in the battery until being commissioned from the ranks. As a “FOO” [Forward Observation Officer], he was wounded severely by a trench mortar while directing fire onto the enemy in the Ypres Salient. He was evacuated and died shortly afterwards.

Of the 19 police mounts in the Battery, St Patrick, or “Paddy” was among the first to fall, killed in action during the fierce fighting at St Julien in 1915. Mistake and Juryman, Vanguard and Crusader and thirteen others would perish by war’s end. The only horse to survive the war was Bunny. A popular letter-writing campaign erupted in Toronto for the safe return of Bunny – but since Bunny wasn’t an officer’s mount he was sold off with the others to Belgian farmers rebuilding their country.

Aside from the 9th Battery, 44 Toronto police officers served in various Artillery units, including subsequent Toronto batteries, and as far afield as the British Army. This number constitutes 28% of the Toronto Police contribution in the First World War. Three of these gunners made the ultimate sacrifice and many more were wounded. For Gallantry, they accounted for one Distinguished Conduct Medal, Two Military Medals, a Meritorious Service Medal and Mention in Despatches.

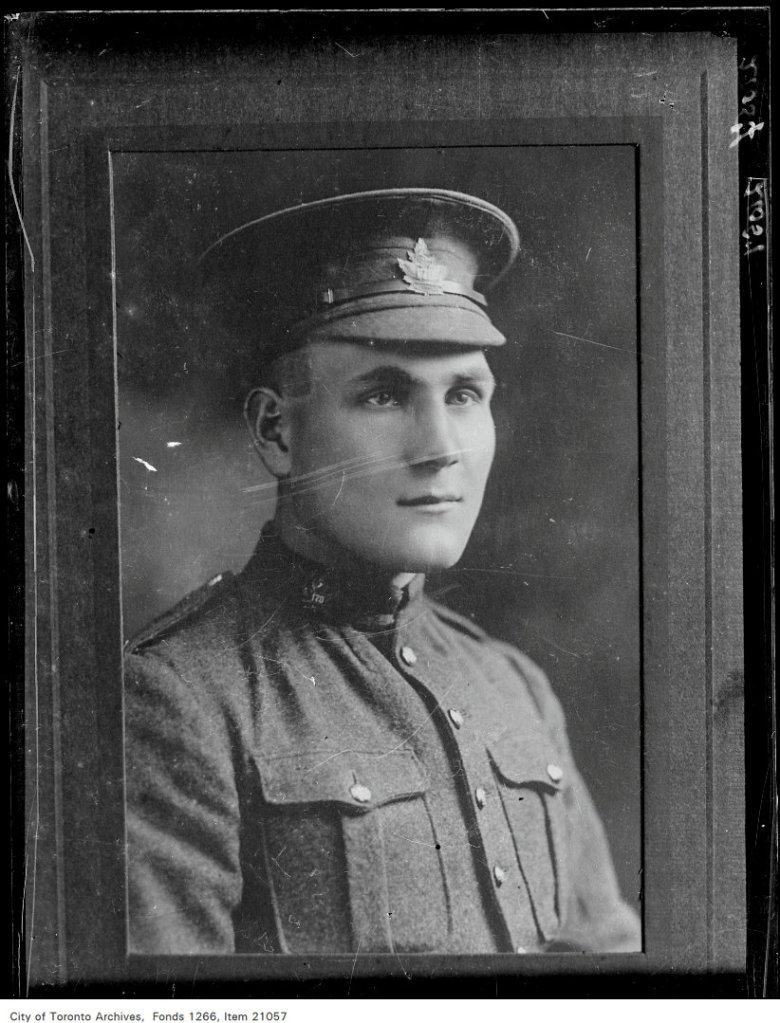

It was shortly after the war that Constable John Faulds, who had served as a gunner in France, was elected first President of the Toronto Police War Veterans Association. Faulds served with Toronto’s 34th Battery. It was known as the “Aquatic Battery” as membership was made up of members of the Toronto Argonaut Club, The Toronto Canoe Club or the Balmy Beach Club. Faulds had risen to the rank of Regimental Sergeant-Major of the the 9th Brigade Canadian Field Artillery. He was awarded a temporary commission that the Toronto Daily Star reported was for bravery in the field.

This gunner, John Faulds was instrumental in founding of our association, in the summer of 1920. He was instrumental in the erection of our memorial tablets at police headquarters; the creation of our annual memorial service; and the establishment of our yearly socials.

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 1266, Item 6818.

During the interwar period policemen who had served as gunners swelled the ranks of our association, and many were members of the Toronto Artillery associations in existence at that time. Men such as Charles Hainer MM who would later die in the line of duty while serving in the Motorcycle Squad.

Unfortunately for a historian, personnel records of the Second World War remain largely private and undigitized, so our records from that time are less detailed. Our contribution to the Artillery this time would be smaller, with many policemen joining the Air Force and Navy unlike in the last war.

At least 10 of our officers are known to have served in the Royal Canadian Artillery. It was a small but solid contingent where half held leadership positions – with a Captain, two Battery Sergeants-Major, and two Sergeants among them.

While their exact contributions during the war still largely unknown, they would serve the city with distinction after the war.

One gunner, Constable Roy Soplet, led a daring rescue during the SS Noronic disaster. In 1949, the pleasure cruise burst into flames overnight in Toronto Harbour with 524 souls on board. Soplet was one of the first officers on scene and without hesitation jumped into the lake and rescued countless panicked swimmers in the darkness. While over a hundred people died in the disaster, not a single one was lost to drowning thanks to Soplet and a few other rescuers.

Another gunner, Constable David Cowan, was celebrated in newspapers for a daring fire rescue in February 1951. Cowan came upon a building engulfed in flames and charged into the upper floor apartments kicking in doors and rescued an elderly woman. When reaching the street with her, he was overcome by smoke and collapsed, spraining the poor woman’s ankle after saving her life.

Later that year, former Battery-Sergeant Major and Acting Patrol Sergeant Joseph Battersby, would be killed in the line of duty. The survivor of two world wars died while trying to secure a downed hydro wire scene.

The soldiers of 7th Toronto Regiment, additionally tasked with Light Urban Search and Rescue, would do well to remember these men.

Postwar, many gunners again joined the ranks of the Toronto Police, including two big personalities that would be active in the Toronto Police War Veterans and Toronto Artillery Associations.

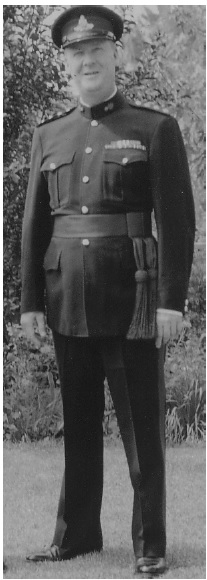

Captain Francis Burtram “Bert” Saul CD was one such character. He was a veteran of the Royal Artillery and the Royal Canadian Artillery. He survived the Dunkirk evacuation, and was wounded during the Normandy Campaign. Starting as a police officer in Forest Hill after the war, he retired as the Staff Inspector of Metro Toronto Police’s Internal Affairs Unit. Bert had also continued service in the militia and was known as the no-nonsense RSM of 42nd Medium Regiment. He was firm, but fair, with a unique sense of humour. He used that experience while drilling cadets at the Police College as a Staff Sergeant in the 1960’s. One now-retired member can still remember a dressing down he got from Saul on the parade square. “Craine!” he barked, “You will be s*** upon from a great height … with incredible accuracy!”

RCAA Annual Report 2001.

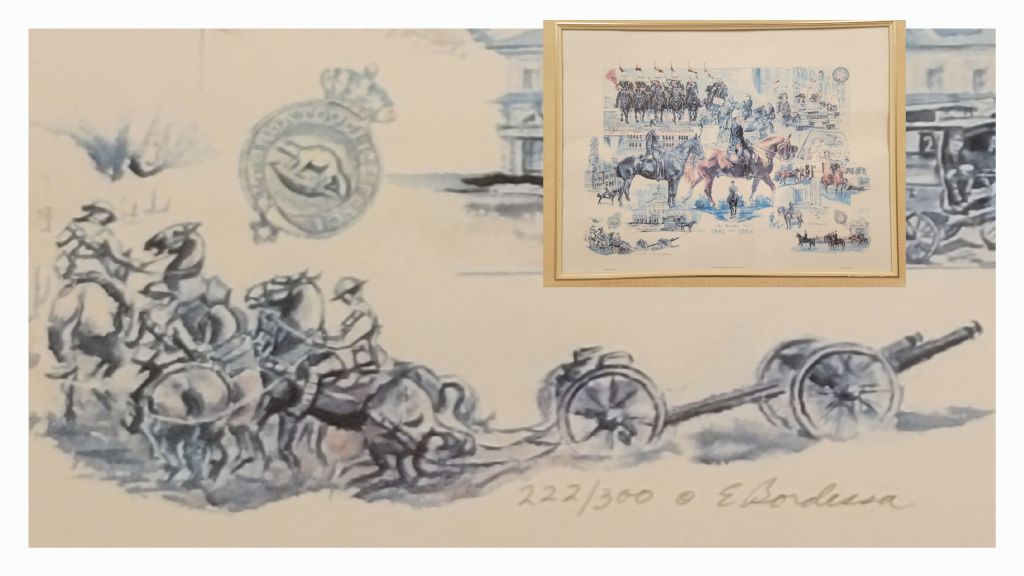

Bert was a founding member of the Toronto Artillery Ex-Sergeants Association and an active member of the Toronto Police War Veterans, who often led our Warrior’s Day Parade contingent. Bert passed in 2001.

Also active in both of our organizations at this time was John Bremner. John served in the Korean War driving ammunition for the guns. After the war he joined the North York Police and was later amalgamated into Metro Toronto Police where he rose to the rank of Staff Sergeant at downtown’s 52 Division. John was involved with the Toronto Artillery Ex-Sergeants association and a was a key member of the Limber Gunners, where he drove his beloved FAT (or Field Artillery Tractor). John passed in 2016.

Bringing us to today, we have in our organizations Dieter Lorenz, who served with the guns in Germany during the Cold War – or should I say the “First” Cold War? Also among us is young officer Kelvin Chu who represents the next generation of police gunners.

I’m now going to close with an excerpt from a letter written by Constable Hugh Banks, a fellow mounted officer who was serving with the 53rd Battery, RCA in England in that tense summer of 1940.

“… I gave up my position to enlist and was finally sent overseas. I left behind my wife and three children. While overseas I received the sad intelligence that my wife had died. I shall never forget as long as I live the kindness bestowed to me by the Officer Commanding and the Chaplain of my unit.

Captain Rae McCleary, the chaplain, has linked himself to me for life by his great understanding sympathy. When he told the lads of my battery of my loss, a movement was started among the troops to raise money to send to Canada for the erection of a headstone on my wife’s grave […] and the stone was carved as directed by a veteran of the last war.

When it appeared that the right thing for me to do was to come home on compassionate grounds to my motherless children, I was eventually paraded before Major-General Victor Odlum. He extended to me a very manly sympathy. His words of counsel and advice I shall never forget. He told me to sit down for a moment or two; he turned to his desk and taking his pen, began to write. In a moment or two he came toward me, evidently touched by my great sorrow, and said, “you will have extra expense when you get home, and I want you to accept this little gift from me,” and he handed me a cheque for $25”.

One thing missing from the letter however, is that back home in Toronto, the head of the Battery’s Welfare Committee, a Mrs. Medland, cared for the three young children herself until Banks returned. It is clear from this letter that all members of the Artillery family – including officers and other ranks and auxiliary associations – come together to take care of one another in times of need.

It is in the spirit of this letter, that the Toronto Police Military Veterans Association makes our donation to the Toronto Artillery Foundation. May your soldiers and their families always be taken care of, and their memories never die.

Thank you, and “Thank Gawd the Guns”.

Postscript

After writing this, a few more details came to light of one Toronto Police Officer, PC Geoffrey Rumble, who joined the Royal Canadian Artillery in the summer of 1940. He would fight in the Italian Campaign and Northwest Europe. By April 1945, Rumble was now a Captain serving as a Forward Observation Officer in the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade. After tough fighting against paratroopers and Hitler Youth in the Dutch town of Zutphen, Captain Rumble was briefly interviewed by war correspondent Douglas Amaron.

Amaron wrote that Rumble had sent a man forward during this fighting to see what was happening. He heard a shout which he interpreted as meaning that it was all right for him to move up, but when he arrived he found the Canadian wrestling with a German in a slit trench.

“I dealt with the German: then we all got into the trench,” Rumble said. “Did you kill him?” asked his Colonel. “I don’t know” Rumble replied “…he was underneath.”

After the war, Rumble rejoined the Toronto Police Department and was promoted to Sergeant. By the end of the 1950s, Rumble was in charge of Drill and Deportment at the Toronto Police College, a role he would turn over to none other than Bert Saul.

Rumble served a total of 42 years with the Toronto Police and died in 2008.

Dignity Memorial, 2008.

Research Sources and Further Reading:

- F. Draper – Annual Report of the Chief Constable of the City of Toronto For the Year 1886.

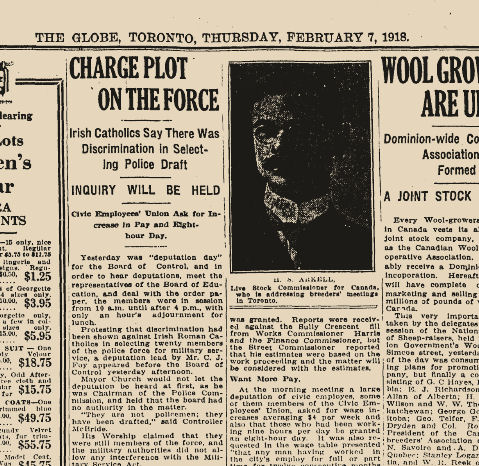

- H. Grassett – Annual Report of the Chief Constable of the City of Toronto For the Year 1918.

- D. Draper – Annual Report of the Chief Constable of the City of Toronto For the Year 1945.

- B. Wardle – The Mounted Squad : An Illustrated History of the Toronto Mounted Police 1886-2000. Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd; Markham 2002.

- C. Mouatt et al. – The 155 year History of the 7th Toronto Regiment, Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery 1866-2021.

- The Royal Canadian Artillery Association. Annual Report 2000-2001. Pages 20-22.

- E. Beno [Ed.]. “Take Post”: The Journal of The Toronto Gunner Community. Edition 10, 11 March 2016. Pages 28-30.

- Library and Archives Canada – Personnel Records of the First World War

- Service File of No. 42459 Charles Chalkin.

- Service File of No. 42480 Thomas Hugh Dundas.

- Service File of No. 42619 William Joseph Sanderson Connor

- Service File of No. 42691 Charles Hainer

- Service File of No. 42538 Ernest John Masters

- Service File of No. 300742 John Faulds

- Library and Archives Canada – Personnel Records of the Second World War

- Service File of No. B9174 Hugh James McKay Banks

- Library and Archives Canada – Military Honours and Awards Citation Cards 1900-1961

- No. 311373 T.D. Crosbie

- No. 42480 T.H. Dundas.

- No. 316952 A.J. Mitcham.

- Library and Archives Canada. Circumstances of Death Registers Card s

- No. 42619 William Connor

- No. 83763 David Hammond Johnson.

- No. 304442 George Brewin Stannage.

- Toronto Public Library. Historical Newspapers Database.

- Toronto Telegram. 1916-06-?? “Death of Lieut. WJS Connor”

- The Globe. 1917-06-30 Page 20. “Policeman’s Bravery.”

- Toronto Daily Star. 1920-09-15 Page 5. “Policemen Form Association.”

- The Globe and Mail. 1941-11-18 Page 6. “Glowing Tribute Paid to Splendid Officer”.

- The Globe and Mail. 1944-10-11 Page 4. “Two Sons Manning Guns Wounded Like Father.”

- Toronto Daily Star. 1945-04-09 Page 1. “Hitler Baby Soldiers Worse Than SS, Canadians Learn.”

- Toronto Daily Star. 1951-02-26 Page 2. “Four Carried to Street, 21 Flee from $4,000 Fire”.

- The Toronto Star 1987-12-15 Page D5 “Policeman Hero of Ship Disaster Ends 45-Year Career.”

- The Globe and Mail 1989-09-16 Page D5. “The Fiery Death”.

- Toronto Star. 2012-02-10. “Untold Story of Toronto’s Real Canadian War Horse.”

- Toronto Police Association – Honour Roll. [https://tpa.ca/honour-roll/] Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Constable Charles F. Hainer, Badge No. 4457

- Sergeant Joseph R. Battersby, Badge No. 860

Special thanks to the members of the MTP Retirees and MTPF Photographs Facebook groups for their added insight.