Motorcycle Cop turned D-Day Landing Craft Commander

Written and Researched by Matthew Scarlino, June 2024.

This year marks the Eightieth anniversary of the famed D-Day Landings of the Second World War. Dwindling in number, it is the last major milestone that veterans of the event will attend in significant numbers.

As 29-year-old Naval Lieutenant Charles Bond looked out from the bridge toward the bloody invasion beaches he didn’t have much time to reflect on his life to that point. Would he ever come back to his Rusholme Road home? Would he see his wife Virginia and their two darling girls ever again? Would he return to patrol the streets of Toronto on his Triumph motorcycle? No, he was too busy directing his ship to its landing point amid the shellfire and fog of war, analyzing the obstacles and wrecks all around him. Juno Beach, the 10-km stretch of Normandy coastline assigned to Canada in the joint Anglo-American invasion of Nazi-Occupied Europe lay ahead. It was D-Day.

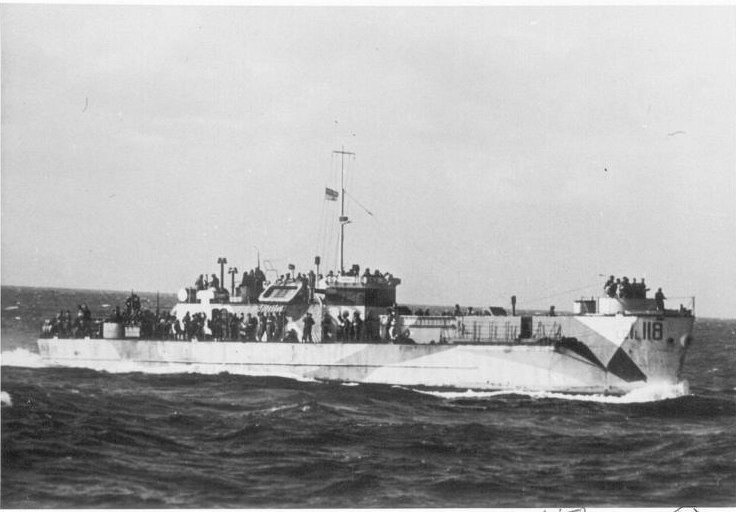

As Commanding Officer of Landing Craft Infantry (Large) Ship 118 or LCI(L) 118, Bond was not only responsible for the lives of his 27 crew, but also the lives of roughly 200 men of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders on board whose job it was to press on the attack in-land, secure the beachhead, and repel expected German counterattacks.

His ship was quite larger than the Landing Craft Assault (LCA) boats that brought in the first waves of troops in smaller batches, etched into the minds of today’s generation through films like Saving Private Ryan. The LCI could disembark greater numbers of troops and equipment down large ramps onto the landing beaches.

Hours earlier, Bond had made the channel crossing from England, his LCI a mere speck among the thousands of ships and airplanes that comprised the greatest seaborne invasion fleet in history. Bond and 11 other LCIs were part of the 262nd LCI Flotilla, carrying the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade, and arrived in the assault area in time to watch the massive pre-dawn naval and aerial bombardment of the coast. The enemy awakened and began returning fire. The flotilla stood by and waited. Around 6:35am, their escort ship, HMS VERSATILE, struck one of many naval mines littering the area. As Bond and his men bobbed in the choppy mine-infested seas, the tension was palpable – they were not scheduled to make their own landing until 10:15.

Assigned to Nan Red Sector of Juno Beach, at St-Aubin-Sur-Mer, all they could do was wait as assault troops finally made their landing behind schedule in chest-deep water, now 8:10am. The entrenched Germans poured fire onto those first waves of Canadian troops. Their artillery and mortars, though by now mostly destroyed, still managed to lob shells toward the ships off the coast.

While the fighting raged and confused reports came in from the shore, the 262nd Flotilla was now circling, about a mile out to sea, awaiting orders. Though the North Shore New Brunswick Regiment reported they were “proceeding according to plan,” La Régiment de la Chaudière advised they were “making progress slowly”. Timelines were being pushed back, and with added reports of sniping, mortar fire and heavy mining still on the beach, Bond’s flotilla was redirected over to Nan White Sector, and circled again off of Bernières-Sur-Mer. Despite Toronto’s Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada having seen some of the heaviest opposition against the Canadians there that morning, it was now deemed the more secure landing zone.

At 11:28, the control frigate HMS WAVENEY gave the long-awaited signal, and it was now time for Bond to make his run in to shore. He had practiced this time and again in England, but training could have hardly replicated what lay ahead. Corpses bobbed in the water. Several LCAs lay wrecked in the landing zones. And even though some engineers had cleared gaps in the approach lanes, the remaining mines and obstacles were now covered from view by high tide. To further complicate matters, there was only 180 yards of available beachfront between groins.

“The LCI’s operation orders,” recorded Naval Historians, “emphasized that it would probably be necessary for the LCI’s to break their way through the obstacles by charging them at full speed so as to disembark their troops well up on the low gradient beach.” They continued: “Had the craft tried to pick their way slowly through the lines of obstacles it is very doubtful that they could have avoided the mines and quite certain that they could not have got far enough up the beach, which had a very flat gradient of about one in a hundred, to give their troops a dry landing. The only course under the circumstances, as had been impressed on all commanding officers in the briefing for the operation, was to think only of landing their troops safely and disregard the safety of their craft. Like the LCAs, the LCIs were expendable.”

After receiving WAVENEY’s signal, “the Flotilla unwound from its circle in the waiting position, formed up in line abreast, [and] worked up to their full 16 knots maximum speed.”

Fanning out, the 12 ships charged through the surf, jockeying and jostling for position around obstacles. A great degree of skill and coordination was required by Bond – all talents well honed during his stint on the Toronto Police Motor Squad. Suddenly, LCI 270 – two ships over from Bond’s, struck a mine in her forward No. 1 Troop Space. Fortunately, that ship’s commander had ordered the troops up on deck, calculating that the mine risk outweighed the risk from enemy fire, and escaped without casualties. One by one other ships of the Flotilla were being holed by obstacles. So far though, LCI 118’s luck held.

At full speed ahead, Bond saw the beach rapidly approaching. LCI 250, with shark’s teeth painted on her bow, could be seen on Bond’s port side, while LCI 252 was off starboard. Seamen on deck watched over the sights of their heavy machineguns, ready to cover the disembarking troops. Soldiers on board clutched their gear, preparing to exit. Bond picked a clear spot of beach and fixated on it.

Suddenly, a blast. LCI 250 struck a mine, exploding near 118’s bridge peppering Bond with shrapnel in his neck and shoulder. His injuries were serious, and his Signalman and Leading Sick Berth Attendant were also wounded in the blast. In the ensuing confusion LCI 250 rammed into 118’s side damaging the port ramp. Obstacles punched holes in its hull.

Mission above all else, the well trained LCI crew leapt into damage control while others ensured an orderly disembarkation as the ship beached. After their rough landing, The North Novas on board descended the ramps and onto the beach. More heavily laden and supplied than the earlier waves of assault troops, it took between 20 and 30 minutes for all troops aboard the LCIs of the 262nd Flotilla to fully disembark. Despite mine and obstacle strikes, and fire from shore, not a single soldier transported by the flotilla was lost in transit.

Bond’s job was not done, however. Treated by a Sick Berth Attendant, he still had to bring LCI 118 back home to port on the Solent, on Britain’s southern coast. One by one the LCIs of the 262nd Flotilla began unbeaching. Due to the cramped conditions there, more yet were damaged. 262 struck two mines flooding her engine room. Kedges were fouled and cut. As Bond’s ship scraped off the beach, she struck a mine somewhere off the starboard quarter, but was still serviceable.

With only seven craft able to sail, the survivors formed up, and at 1:45pm this sorry convoy limped home, LCI 118 leading.

Back in Blighty

Upon landing at the frenzied port, Bond turned over his ship and gathered his injured men. Holding his neck, he walked to a taxi stand and hailed a cab. “We’re just back from France,” he calmly stated, and “we were wounded a little.” Away they went to hospital. Upon arrival, a startled hospital attendant hurriedly admitted the men, thus ending for them what came to be known as “The Longest Day”.

Back in port, naval authorities recorded the damage to LCI(L)-118 thusly: “Damaged by the mine set off by 250; port ramp had to be jettisoned after being rammed by 250; kedge had to be cut after being fouled by 252; starboard screw sheered off by mine while unbeaching and three holes pushed through the ship’s bottom, two of them into engine room.”

It was no small miracle that LCI 118 survived, along with her commander. The superstitious among the crew were not surprised, however. After all, they had named her “The Lucky Canuck”.

Postscript

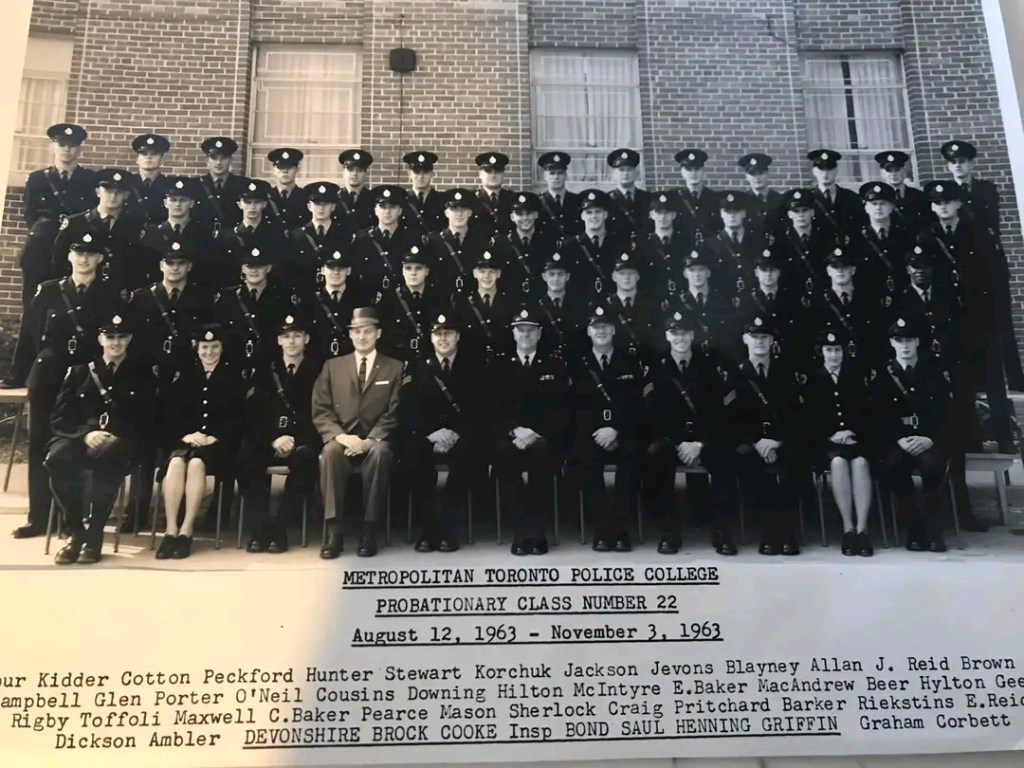

Charles Bond joined the Toronto Police Force on December 15th, 1936. Sworn in as Police Constable 152, he served out of No. 4 (Dundas East) Police Station, first walking the beat, and then on the motorcycle squad. He stood 6’2 and weighed 230lbs, a large man in his time. Bond’s first brush with death came a few minutes after midnight on April 2nd, 1939. While on his beat the keen-eyed policeman observed a stolen vehicle whose license plate he had memorized. Parked on the east side of Mutual Street north of Dundas, Bond waited until car thief Thomas Martin returned to the scene. “I shouted for him to stop, but he only kept going.” The suspect entered the vehicle while Bond jumped onto the running boards, moments too late. Speeding off, the driver began swerving into telephone and hydro poles attempting to scrape the officer off the car. His commands unheeded and fearing the man would kill him, Bond fired a warning shot through the door. It was ineffective. Bond fired another round, grazing Martin in the arm. “I did not want to fire the shot, but I began to think I might get seriously hurt if I didn’t stop him.” Martin bailed out of the vehicle and was promptly apprehended. He was recognized as a local break-in artist. This arrest impressed Bond’s superiors who promoted him to First Class Constable six months early.

After Bond’s wartime service (1940-45), Charlie Bond, as he was known by then, continued to climb the ranks, serving in various roles. His seven years as head of the Metro Police College were remembered as his fondest. After 35 years in uniform, the incident in 1939 remained the only time he had to fire his gun. Bond capped his career as Superintendent in charge of all operations in the borough of North York. He retired to his farm in 1971 with his loving wife Violet.

Charles Ralph Bond died in 1991.

Dedicated to the brave crews of the Royal Canadian Navy’s LCI Flotillas.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Toronto Police Force. Chief’s Annual Reports for the Years 1939-46. Carswell Ltd Printers, Toronto.

- RCN Historical Section. The RCN’s Part in the Invasion of France – The 262nd Flotilla Beaches. Pages 103-107. London, 1944-45.

- WAB Douglas et al. A Blue Water Navy: The Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War, 1943 – 1945, Volume II Part 2. Chapter Seventeen, pages 263-266. Vanwell Publishing Ltd, St Catherines.

- R. Foot. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Article: Canada on D-Day: Juno Beach. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/juno-beach (Retrieved 5 June 2024.)

- For Posterity’s Sake: A Royal Canadian Navy Historical Project. Charles Ralph Bond, Lieutenant O-7440, RCNVR. http://www.forposterityssake.ca/CTB-BIO/MEM001356.htm (Retrieved 5 June 2024.)

- For Posterity’s Sake: A Royal Canadian Navy Historical Project.LCI(L) 118.http://www.forposterityssake.ca/Navy/LCIL118.htm (Retrieved 5 June 2024.)

- NavSource Online: Amphibious Photo Archive. HMC LCI(L)-118. https://www.navsource.org/archives/10/15/150118.htm (Retrieved 5 June 2024.)

- The Globe and Mail (1939 April 3rd) Page 5. “Driver is Shot by PC Hanging to Side of Car”.

- The Toronto Daily Star (1942, October 3rd) Page 2. “Toronto Men Among Graduates from Royal Roads”.

- The Toronto Daily Star (1944, June 9th) Page 3. “Wounded Back in Blighty, 2 Take Taxi to Hospital”.

- The Globe and Mail (1944, June 9th) Page 4. “Wounded in Landing, 3 Take Cab to Hospital”.

- The Toronto Daily Star (1944, August 21st) Page 1. “Commander of an Allied LCI”.

- The Toronto Daily Star (1945, September 8th) Page 3. “Police War Veterans Given Promotions”.